In addition to the Annual "Dubious Polling" Awards, veteran pollsters Bishop & Moore will now be writing the "PollSkeptics Report" column twice-a-month.

Each of us has been involved in the polling enterprise for over thirty-five years, so this skepticism about media polling is neither fanciful nor fleeting.

Our skepticism focuses primarily on the results of major media polls, which shape our collective vision of what the public thinks and wants.

At the same time, we both believe that well-designed polls, with scientifically-chosen samples, can produce useful insights into the public’s thinking. Too often, they do not.

We believe that in most cases, the fault lies not with the limitations of polls themselves, but rather with the pollsters and the journalists who design and interpret them.

Our criticisms of media polls arise not out of any partisan considerations, but out of a conviction that such polls frequently distort, if not mangle completely, what more valid measures of public opinion would show – if the polls were conducted more rigorously.

In our PollSkeptics Report column, we will illustrate these concerns using media poll results as prime examples.

There is a foundation for our many critiques to come – Bishop’s The Illusion of Public Opinion: Fact and Artifact in American Public Opinion Polls and Moore’s The Opinion Makers: An Insider Exposes the Truth Behind the Polls. Our column for iMediaEthics will extend the arguments in our books to current polling results.

Skepticism Justified

That it’s reasonable to be skeptics is all too evident in the spate of recent polls dealing with health care legislation.

As Gary Langer of ABC recently noted, polls leading up to the passage of the legislation provided wildly contradictory findings about the American public – from a CNN poll which showed a 20-point margin against passing the healthcare bill, to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll showing a 4-point margin in favor. Several other polls produced varying results somewhere in between.

Such conflicting poll results are not unusual.

On “cap and trade” legislation, for example, CNN recently found a large majority of the public in favor, by a margin of 23 percentage points.

An earlier Zogby poll reported a large majority opposed, by a 27-point margin – a swing of 50 points. Other polls on this subject have generated results in between these extremes.

Faulty Polling Practices

We hold pollsters accountable for these conflicting results because of faulty survey practices that have become the norm in much of current media polling.

A realistic public is comprised of people who have developed solid opinions, as well as those who have not thought about a subject and have therefore not yet formed an opinion. But instead of providing such an actual and comprehensive picture of the public, many pollsters prefer instead to portray the public as fully engaged and opinionated, with all but a small percentage having a position on every conceivable subject.

Zogby, for example, reported that only 13 percent of Americans had “no opinion” on “cap and trade” legislation; CNN reported just 3 percent.

The truth is, as a Pew poll revealed, the vast majority of Americans don’t even know what “cap and trade” means, much less whether it would be an effective way to reduce greenhouse gases.

Pollsters typically produce the illusion of an opinionated public by a variety of techniques that, wittingly or unwittingly, manipulate respondents into coming up with opinions, even when they don’t have them.

In the “cap and trade” case, for example, pollsters first read respondents their explanations of this legislation and then immediately asked them to give an opinion on it in a forced-choice question, which offered no explicit opportunity to say “don’t know” or “no opinion.”

This type of question pressures respondents to choose one of the alternatives presented in the question, even when they may prefer to indicate “no opinion.”

Not knowing anything about the issue, but pressed to come up with an answer, respondents will generally base their choices on the information they have received from the interviewer, or on a vague disposition invoked by a word or phrase in the question itself (e.g. something about “the government”).

Such responses are hardly valid indicators of what the larger public is really thinking about the issue at hand.

This point is reinforced by the results of the “cap and trade” polls mentioned earlier. Most respondents knew nothing about the issue and thus relied on the “explanations” provided in the questionnaire as the basis of their choices. Obviously, CNN’s explanation was quite different from Zogby’s – leading the respondents in the CNN sample to come up with diametrically opposite “opinions” from respondents in the Zogby sample.

Both polls could not be right. In fact, neither reflected the public’s lack of engagement on the issue.

Each polling organization essentially manufactured its own version of “public opinion,” based on its unique question wording.

This process of influencing respondents, and thus distorting what valid measures of public opinion would show, is all too commonplace.

Pollsters Claim: Accurate Election Results Validate Their Public Policy Polls

In defense of their practices, most pollsters argue that, because their final pre-election polls can (more or less) accurately predict the outcome, we consumers should also trust their poll findings on policy issues as well.

But, in fact, the polls often do a lousy job of tracking elections. The last presidential election is a case in point.

We acknowledge that most of the major media polls usually come reasonably close to predicting the outcome of presidential elections in their final polls, as they did in 2008. However, during the campaign itself, the pollsters provided wildly different estimates of which candidates the electorate preferred.

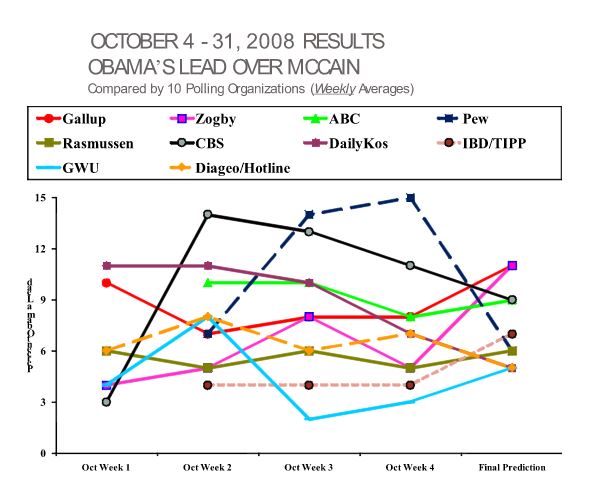

Let’s look at the polls’ collective performance during the last month of the presidential campaign. The accompanying chart shows the weekly average of the ten most frequently released polls in October, 2008.

Note that even though the poll results tend to converge in the final predictions, the trend lines reported by the polls during the last month of the campaign vary substantially.

Yes, they all show Obama, not McCain, in the lead, but some suggest the lead was so minimal, McCain might well win.

Others show a fairly comfortable lead for Obama throughout the month.

And a couple show major fluctuations, with Obama’s lead surging or declining by 9 to 10 points from one week to the next.

Not Trusting the Polls

If the major media polls don’t give us a coherent story about the election campaign, they are even worse in describing public opinion on complex policy issues.

At least with elections, the object being measured in the polls is simple and concrete – which candidate do the respondents prefer?

On public policy issues, the preference being measured is generally much more abstract and complex.

Furthermore, there are many people who don’t pay much attention to policy issues, just as there are many voters who don’t pay attention to an election early on in the campaign.

But the public’s lack of engagement, and lack of understanding on many issues, do not deter media pollsters, who pressure their respondents to provide answers – answers which, in too many circumstances, do not reflect anything at all like the public’s actual awareness, knowledge, and judgment.

So, as a general rule, we do not trust results from poorly designed media polls that pressure respondents to produce opinions they don’t have, or that influence respondents by giving them (often biased) information most members of the general public don’t have.

That doesn’t mean we think all such polls are useless. Sometimes, despite their faults, they can provide clues about the nature of public opinion.

They just can’t (and shouldn’t) be interpreted literally. Unfortunately, a literal reading of media polls is the norm for the vast majority of news reports and media outlets today.

Everyone who relies on poll results for insights into reality needs to heed the warning: Caveat Emptor! No one, not just the two of us, can reasonably avoid being a Poll Skeptic.

George Bishop is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Graduate Certificate Program in Public Opinion & Survey Research at the University of Cincinnati. His most recent book, The Illusion of Public Opinion: Fact and Artifact in American Public Opinion Polls (Rowman & Littlefield, 2005) was included in Choice Magazine’s list of outstanding academic titles for 2005 (January 2006 issue).

David W. Moore is a Senior Fellow with the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire. He is a former Vice President of the Gallup Organization and was a senior editor with the Gallup Poll for thirteen years. He is author of The Opinion Makers: An Insider Exposes the Truth Behind the Polls (Beacon, 2008; trade paperback edition, 2009). Publishers’ Weekly refers to it as a “succinct and damning critique…Keen and witty throughout.”

The simple dichotomy used here between informed, stable opinion and uninformed, unstable responses is not useful in practice and is indefensible in theory. Most of us, most of the time, on most questions fit neither label. Opinions do not usually come out of nowhere (random responses) or depend entirely on a stimulus (all provide the same response). They often come from existing opinions linked to a new object. In focus groups, the idea is to find out predispositions to respond by trying out a new ad, for instance, and linking it to more established characteristics. Similar practices apply for other techniques, as in jurimetrics. How reliable and stable are these measured predispositions to respond? That depends, and is a topic that this column just defines away.

In Response to Douglas Rose:

You have raised an important issue, and one on which I think you and I would find a great deal of agreement. For example, I certainly agree with the notion that there is a continuum from informed, stable opinion at one end of the spectrum to uninformed, unstable responses at the other end. An academic study of opinion formation and change would want to be able to measure intensity along the whole range of that spectrum.

We’d also like to know at what intensity level the opinion has an impact on the person’s behavior. If people opine that they oppose a certain policy, for example, how intensely do they have to feel in order for that opposition to have an impact on their behavior – such as voting against a candidate who took the opposite stance, or at the very least taking some step to communicate that view to their representatives? In fact, this is an area of research in which I am presently engaged.

It’s important to remember, however, that our focus in this column is not on polls that are conducted for research purposes, but rather on the media polls which do indeed make distinctions between one end of the spectrum and the other – between opinions they feel are meritorious to report as the will of the people, and those which they say can be classified as non-opinion. Along that whole spectrum, media pollster almost universally end up including as “public opinion” the views of many people who themselves would be willing to admit they don’t have an opinion (if given the chance), or who clearly had no opinion on the subject before they were pumped full of limited (and thus inevitably biased) information about the issue at hand.

A side note: The very fact that respondents are given information that the general public does not have means the sample no longer represents the general population. At best, the results are hypothetical about what the public might think if everyone were given the same information as the respondents. But pollsters never make a distinction between their hypothetical results and the results they get by asking respondents about subjects without first giving the respondents information. They treat everything as though their results portray what the public really wants.

On the broader issue of opinion spectrum, whether we like it or not, the fact is that media pollsters all the time make a distinction between opinion at one end of the spectrum and non-opinion somewhere at the other end. And their results are treated as virtually the Holy Grail. Their cut-off bar is always so low that typically they report about 90% people with an opinion on almost every conceivable issue. This is clearly not realistic.

From a political perspective, it’s very difficult to argue that if legislators are going to be given a picture of the public, the one set of numbers that will be touted most saliently will be those that include for many people the most shallow of impressions – and in many cases, impressions that have been essentially created by the pollsters’ questionnaire (because of unique question wording and context).

Again, while you and I may not like any dichotomous distinction between opinion and non-opinion, it is a fact of life that media pollsters report such a dichotomy. Sometimes, pollsters will ask respondents “Do you favor or oppose policy X, or don’t you have an opinion?” This indicates that pollsters recognize that offering respondents the opportunity to say they have no opinion can be an important element of what they report. But 1) they rarely do that, because it’s more interesting to make it appear as though the vast majority of Americans have a stable, informed opinion, and 2) when pollsters do explicitly ask for non-opinion, they never justify why it was important to do it in that case, and not all the other times.

Having worked for 13 years with Gallup, and having examined literally thousands of poll results from other media pollsters as well, I have concluded that there is no clear theoretical rationale that underlies when pollsters ask for non-opinion and when they try to force opinions. The practical rationale is almost always this – would the story being reported by the press be enhanced by showing a large proportion of undecided or not? If it seems newsworthy to report how confused or unengaged the public is, that’s when the cut-off point between opinion and non-opinion will be shifted down the spectrum to include more non-opinion. But most of the time, it’s more newsworthy to portray the public as almost completely engaged in every issue.

I very much agree with you about the important research question: How reliable and stable are opinion measurements? Our argument is that right now, the media pollsters’ cut-off points provide their answers to your question. They implicitly treat virtually any response, however whimsical, however uninformed, however much it’s been manipulated by the questionnaire itself, as reliable and stable – and thus worthy as being treated as the “will of the public.”

I disagree. I think the media pollsters can find a more realistic cut-off between opinion and non-opinion. Their current practice is, in my view, very misleading.