Newspapers (Credit: PublicDomainPictures.net)

Suicide is a public health crisis in the U.S., yet many media outlets continue to irresponsibly report on it. The most recent example is the June 5 death of designer Kate Spade. Just this past week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed that, “In 2016, nearly 45,000 Americans age 10 or older died by suicide” and that suicide is the “10th leading cause of death.”

While careful guidelines for reporting on suicide exist, news outlets, including the New York Post, seemingly ignored those guidelines by reporting details such as how Spade was found, the way she died and what her alleged note said. Spade’s husband, Andy Spade, said he was “appalled” that the contents of the note was “so heartlessly shared with the media” and added that he hasn’t seen the note.

“Obviously the reporting recommendations on suicide are to not provide detail like that,” Ken Norton, the executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, New Hampshire, told iMediaEthics. “Part of the question to me is why do we need that level of detail? Why isn’t it sufficient to say she died? To paint the picture of [how she died] is first of all pretty abhorrent for her family and friends and also likely traumatizing and triggering for other people,” Norton added.

The Society of Professional Journalists’ Lynn Walsh emphasized the need to balance between providing information to the public and minimizing harm. Noting that suicide is an area that traditionally has been “shied away” from, Walsh, who was president of the organization from 2016 to 2017, suggested news outlets are “most tasteful and respect those involved.”

Reporting on suicide is an important ethical area that iMediaEthics has focused on over the years because irresponsible reporting on suicide can lead to copycat deaths or traumatize the public or family members of the deceased, whereas the news media has an opportunity to point those in need toward help. News outlets shouldn’t speculate or provide too much detail and should consider careful phrasing; Norton explained even phrasing reports as “committed suicide” is problematic because “committed is associated with negative things” like crimes or hospitalization.

In addition, Walsh recommended outlets avoid the word “suicide” in the headline. “Maybe not specifically in talking about how it happened, is it really important that people know how they committed suicide?” she asked.

Walsh advised news outlets include information about how to find help and resources. “The important thing if you’re a reporter covering this,” she said, is to “think about if this was your family, if this is someone you knew. These are people at the end of the day,” she reminded. “Is it important how the person committed suicide? I would say in a lot of cases not.” Exceptions may include if an investigation or questions surround the death, but “at the onset,” just reporting the fact of a death should suffice.

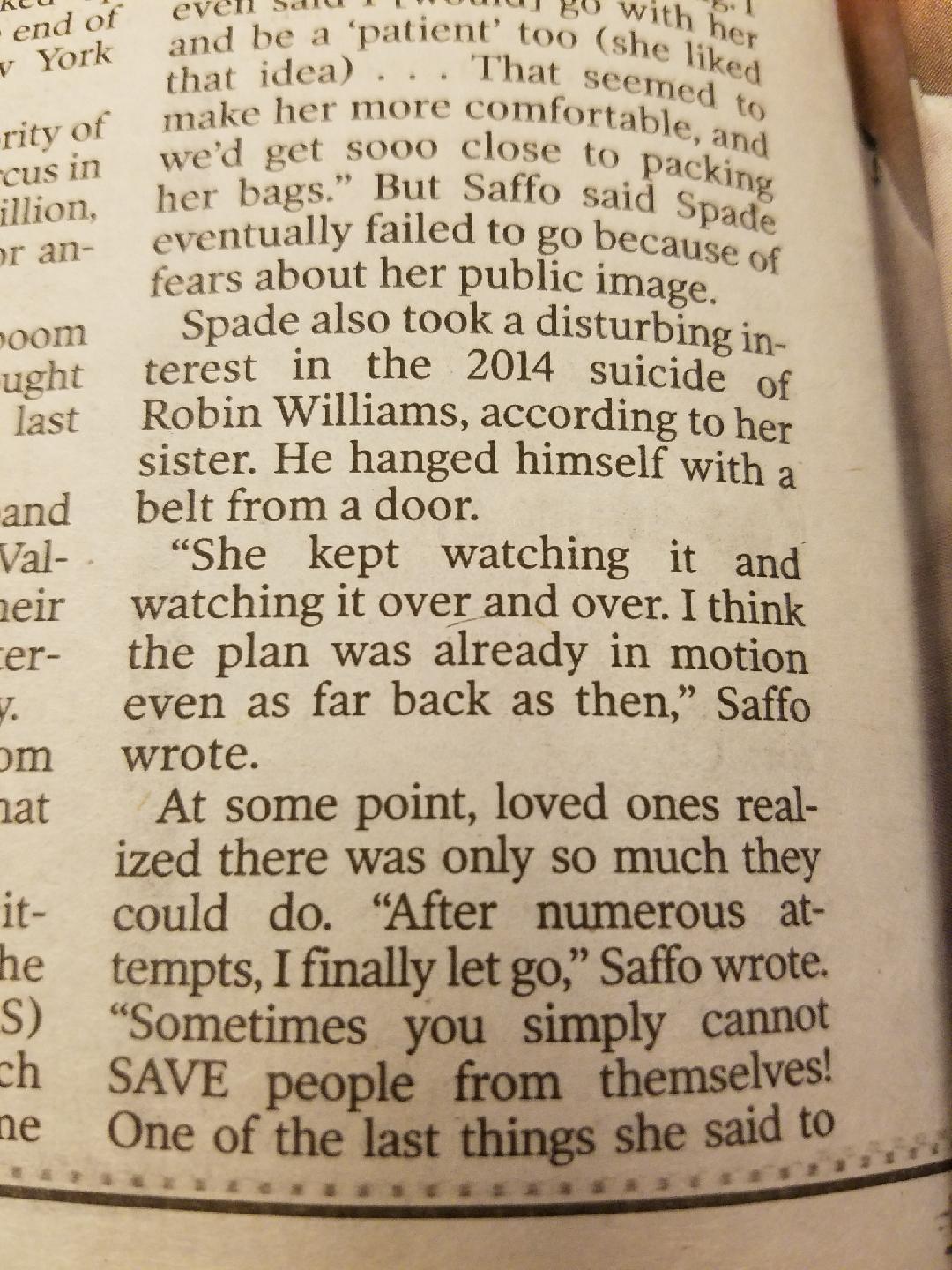

Instead of focusing on the details of the death, Norton recommended that news outlets include information on how people can get help, noting that calls to the national suicide prevention lifeline went up after Robin Williams’ death. Many news outlets blatantly invaded privacy and published prurient details about Williams, as iMediaEthics documented at the time. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline saw a significant increase in calls from people seeking help, Newsweek reported.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline phone line, which is free and open 24 hours a day, is 1-800-273-8255.

As an alternative, Norton suggested news outlets highlight “prevention, what local resources are available maybe finding a person who has attempted suicide to talk about the hope and resilience and recovery they found would be much better angles and much healthier angles for reporting on then going into detail” about specific deaths by suicide. “It’s very very sad and it’s sad especially for someone to have a young daughter that these reports will be online and available forever,” Norton said.

“Sadly, celebrity deaths seem to be just like celebrity lives,” Norton said. “We seem to think we’re entitled to all these details.”

As for reporting on any alleged note, Norton said news outlets shouldn’t report what the notes say, but rather if they need to report anything, just the fact that it exists. Likewise, Walsh said, “As journalists, we should be concerned that we are potentially providing information before loved ones have a chance to sit down with authorities or sit down with one another and have a chance to grieve.” Spade’s husband’s statement said in part, “I have yet to see any note left behind and am appalled that a private message to my daughter has been so heartlessly shared with the media.”

Walsh noted the difference between some publications that are “more tabloid and less journalism,” and may publish more sensational or graphic information but still news outlets must consider what to publish. “In this day and age, the information is probably going to get published,” she said. “We, as professional journalists, can really take it upon ourselves to set a higher standard.”

For journalists debating whether to publish or not, the SPJ has an ethics hotline available by phone and e-mail. Walsh pointed to the SPJ ethics code, explaining, “Our code is meant to be used holistically, but in times of reporting on and covering suicides, journalists should especially pay attention to this section, including:

- “‘Balance the public’s need for information against potential harm or discomfort. Pursuit of the news is not a license for arrogance or undue intrusiveness.

- Show compassion for those who may be affected by news coverage. Use heightened sensitivity when dealing with juveniles, victims of sex crimes, and sources or subjects who are inexperienced or unable to give consent. Consider cultural differences in approach and treatment.

- Recognize that legal access to information differs from an ethical justification to publish or broadcast.'”

Suicide “is a significant public health problem that is chronically underfunded by comparison to cancer or heart disease or other leading causes of death,” Norton said. “Suicide death is a tragedy — why do we accept that 45,000 deaths a year is acceptable?”

News Coverage of Spade’s Death

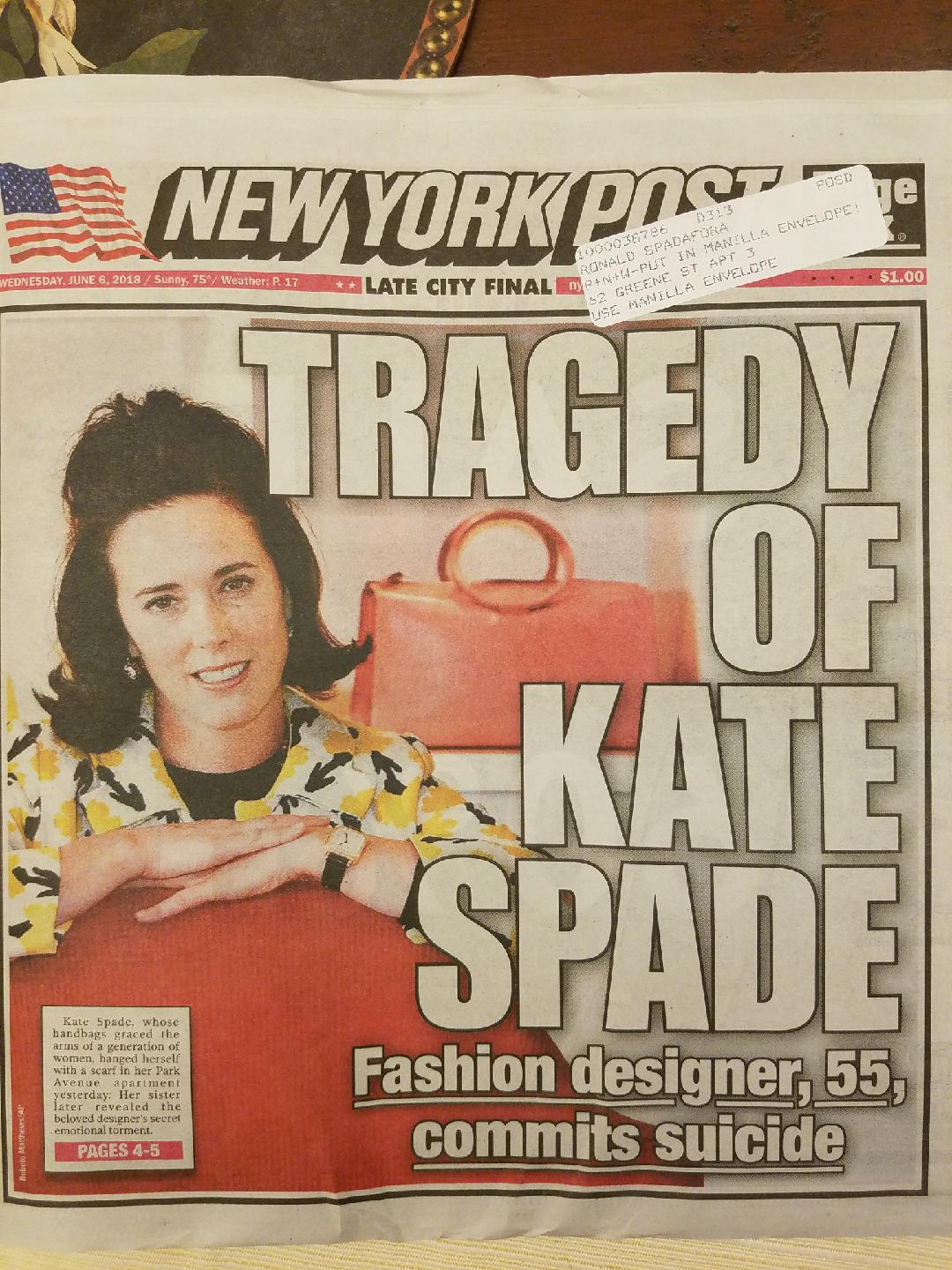

The New York Post’s June 6 front-page story used the phrase “commits suicide” in large letters on the front page, and the story inside compared her death to other celebrities who have died by suicide.

In an online June 5 article headlined, “Kate Spade’s suicide note had a message for her daughter,” the New York Post reported details from Spade’s alleged suicide note, quoting from it.

The Post wasn’t alone, though. The Associated Press reported how Spade died, who found her, that there was a note and cited an anonymous source describing how Spade was found. iMediaEthics asked the Post and AP for a response and reasoning for publishing such details but received no response.

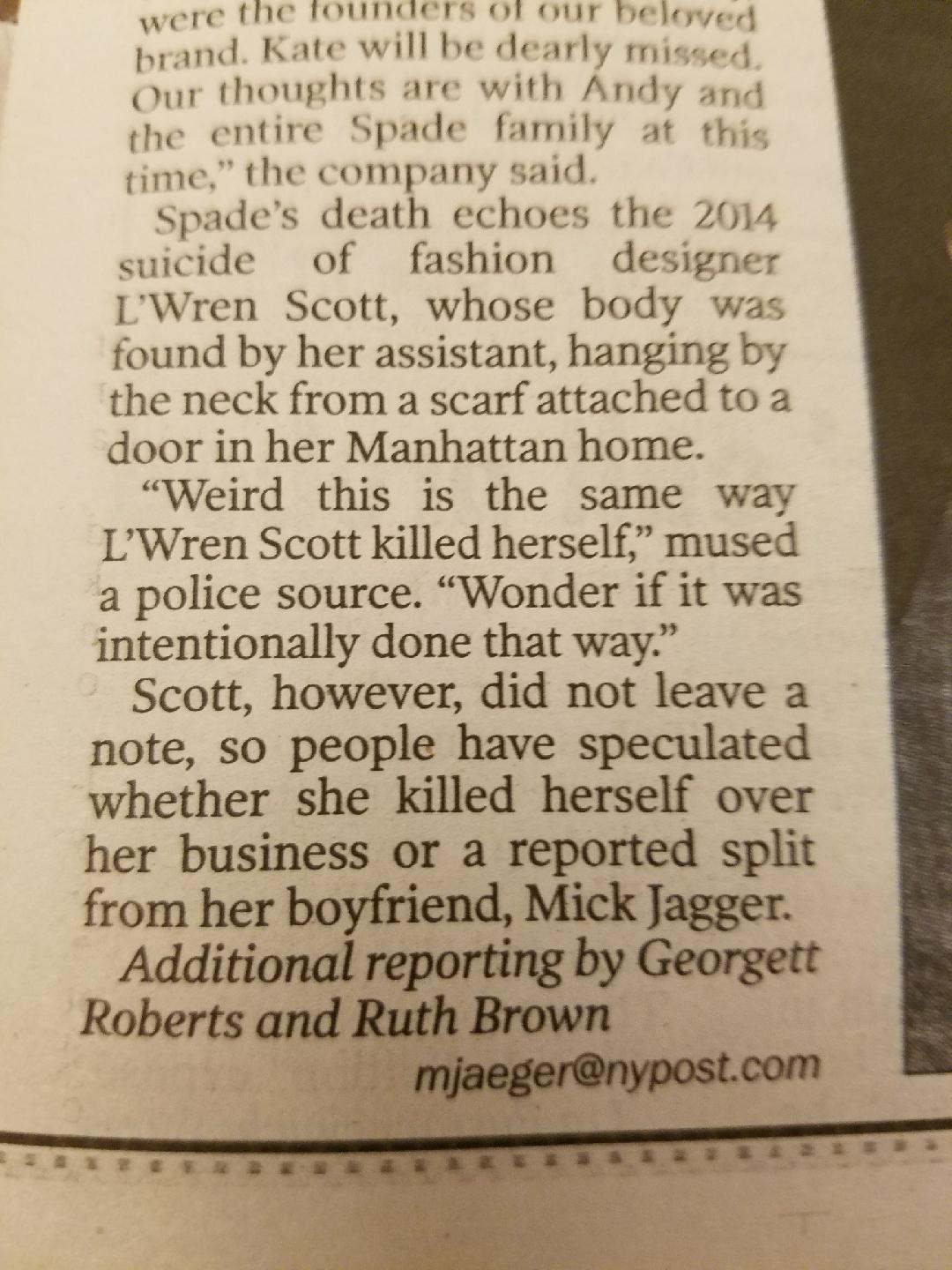

The New York Times described how she died. and that the note said it wasn’t her daughter’s fault. According to the Daily Beast, the New York Times‘s article originally reported that Spade was found “hanging from a red scarf tied to a doorknob.” That detail appears to no longer be in the Times‘ story.

The Times‘ article currently includes other details about Spade’s death, including where she was found, the method of death, and information from her suicide note. iMediaEthics has asked the Times why it included such details, why it removed other details and if it received complaints. Times spokesperson Eileen Murphy told iMediaEthics, “Like most stories that start as breaking news, this one was updated multiple times throughout the day (more than 80, as a matter of fact.) The story transformed from two sentences to a front page print and web story in the course of 12 hours. Obviously it becomes less news and more of an appreciation of a life as the story progresses. ”