10 MINUTES ON GRAND STREET: One third of the bike riders observed on Grand Street, Soho, New York City within 10 minutes violated the one-way street signage and rode the wrong way. Numerous arrows that point the safe direction are ignored. (Credit: Rhonda Roland Shearer)

In response to the current controversy over the expansion of bike lanes in New York City, Mayor Bloomberg’s senior advisor, Howard Wolfson, recently issued a statement defending the policy. The first defense he cited was the popularity of the program:

“The majority of New Yorkers support bike lanes. According to the most recent Quinnipiac poll, 54 percent of New York City voters say more bike lanes are good ‘because it’s greener and healthier for people to ride their bicycles,’ while 39 percent say bike lanes are bad ‘because it leaves less room for cars which increases traffic.'”

Given that a recent article in the Wall Street Journal reports that the mayor and his administration may have been spinning safety data to support the bike lane policy, you might think that Mayor Bloomberg himself had conducted the Quinnipiac poll, or commissioned it, or at the very least influenced its results in some way or another. How else could you account for the finding that a majority of New York City voters actually said increasing bike lanes is good because it’s “healthier for people to ride their bicycles”?

Is th at the first thing New Yorkers really think about when asked about bike lanes – how healthy it is for the bike riders? If so, kudos to them, for thinking of others. I live in New Hampshire, and when I asked a whole bunch of friends (admittedly not a representative sample of anything, not even of all my friends) whether they would want an expansion of bike lanes around our area, not one person said “yes” because they felt it was healthier for other people to ride bikes.

at the first thing New Yorkers really think about when asked about bike lanes – how healthy it is for the bike riders? If so, kudos to them, for thinking of others. I live in New Hampshire, and when I asked a whole bunch of friends (admittedly not a representative sample of anything, not even of all my friends) whether they would want an expansion of bike lanes around our area, not one person said “yes” because they felt it was healthier for other people to ride bikes.

Well, as it turns out, most New Yorkers probably wouldn’t give that reason either, if they were allowed to express their opinions in their own words. It was Quinnipiac that actually formulated the response, which in legal terms might be called “leading the witness.”

Stacking the Deck

Even before asking the loaded question, however, the Quinnipiac University Poll stacked the deck in favor of bike lanes. They did so by first informing respondents that “there has been an expansion of bicycle lanes in New York City.”

How does that stack the deck? For almost all issues, even the most contentious, there is always a significant segment of the population that is not engaged – people who couldn’t care less one way or the other what happens. But once the pollster pretends as though everybody is informed (and makes that appear to be the case, by actually informing the respondents in the sample), and then asks all respondents to opine about the issue, the sample is fatally contaminated. It no longer represents the general public, many of whom are simply uninformed or otherwise unengaged in the issue.

A more objective approach would have been to ask whether the respondents even knew of the expansion. After all, Bloomberg’s senior adviser Wolfson noted that in the past four years, the city has added 255 miles of bike lanes, while the city has over 6,000 miles of streets. This would suggest that probably a lot of residents were not even aware of the expansion – perhaps especially people who travel mostly by subway, or others who are generally clueless about anything.

WATCH OUT! Within the same 10 minutes, New York City’s Grand Street bike lane is awash in bike riders violating one-way-street traffic rules–like this woman and child riding a tandem bike the wrong direction. (Credit: Rhonda Roland Shearer) |

How many city residents are not engaged in the issue? Based on polling I’ve done and seen on jillions of other issues over the years, I would estimate about a third to a half of New York City voters don’t really care one way or the other, either because they don’t see bike lanes as affecting them, or because they simply haven’t been paying attention to the issue. (Of course, this is only a guess. What we need is for the pollster to ask the question, rather than taint the sample by giving respondents information.)

Nevertheless, Quinnipiac asked all sample respondents – regardless of their knowledge or engagement in the issue – the following question:

As you may know, there has been an expansion of bicycle lanes in New York City. Which comes closer to your point of view:

A) This is a good thing because it’s greener and healthier for people to ride their bicycle [sic], or

B) This is a bad thing because it leaves less room for cars which increases traffic.

There are two major problems with this question.

First, it is a “forced choice” question, which means that there is no explicit option for a person to say they have “no opinion.” This format is used by pollsters when they want to suppress the percentage of people who are classified as “unsure.” (One reason pollsters do this is that they feel it’s not newsworthy if, say, 30% to 40% or more of the public has no opinion.)

How do people with “no opinion” choose an option when an interviewer pressures them to come up with one? Typically, they succumb to the phenomenon of “response acquiescence” – a term which means they usually respond in a positive, rather than negative, manner. If that happened here, and I’d be surprised if it didn’t, that would mean an overestimate of the percentage who support the expansion of bike lanes.

Second, the question could have asked whether the respondents supported or opposed the policy (or had no opinion). But instead, the pollster put words into the respondents’ mouths, by giving reasons for each choice. That’s how Wolfson could say that a majority of New York City voters believed bike lanes were “healthier for people to ride their bicycles,” though it’s highly unlikely many people would have made that statement on their own.

The net result of the question phrasing, I believe, is to lead the respondents toward selecting option A, because it sounds good to have a policy that is “green” and “healthy” – even though there is the minor inconvenience of increased traffic.

On New York City’s Grand Street, 2/3 of the bike riders observed within 10 minutes correctly followed traffic rules, like man depicted above. Note the arrows. (Credit: Rhonda Roland Shearer) |

Of course, I could be wrong on this – it’s a matter of opinion which of the two alternatives sounds more positive to someone who otherwise doesn’t know anything about the issue. But that’s the point – rather than ask a tendentious question, Quinnipiac researchers could have asked an objective one. They did not.

So, can we believe the finding that a majority of New York City voters support the Mayor’s policy? Not so, I would argue, if the only source is the Quinnipiac poll. It’s possible that even a majority don’t have an opinion one way or the other – though a good poll would let us know.

Manufacturing Opinion

This example is yet another case when a poll is used to manufacture a “public opinion” that appears plausible, but that poll watchers really cannot trust to be realistic. Nevertheless, it is being used to help counter dissent from people who have found the expansion of bike lanes objectionable for various reasons. As a pollster, I wouldn’t want to take sides – but I would want to present a realistic picture of the public on the issue. Unfortunately, this poll does not meet that standard.

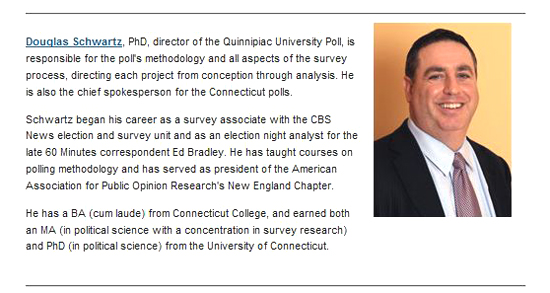

Why do pollsters, such as Quinnipiac, engage in such false efforts? I talked with Doug Schwartz, the poll’s director, and he assured me that Mayor Bloomberg had nothing whatsoever to do with the poll – and I believe him. I never really thought the mayor had any input, but I wanted to be able to say so in print.

Quinnipiac’s Doug Schwartz. (Credit: Quinnipiac) |

I also asked Doug a few questions about the design of the bike lane question, but instead of answering them on the record, he deferred to Mickey Carroll, the Director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute (which houses the Quinnipiac University Poll, directed by Doug Schwartz).

Here are the questions I asked:

- Why didn’t you ask an awareness question at the beginning, to find out which respondents knew about the bike lane issue and which had never heard of it?

- Why did you phrase the question about bike lanes the way you did, giving reasons for and against the issue, rather than a straight-forward “favor” or “oppose” format? Wouldn’t the latter provide a more objective measure of what people were thinking, rather than the format you used? By giving people reasons for and against the issue, reasons that they may not have thought about, aren’t you biasing the question article?

- Why did you use a forced-choice format, providing no explicit “unsure” option – such as “or don’t you have an opinion one way or the other?” or “or are you unsure?” – some phrase like that? When you ask everyone the question, regardless of whether they even knew about it before the poll began, and then use a forced-choice format that pressures respondents to come up with an immediate answer, aren’t you artificially inflating the percentage of people who appear to have an opinion about the issue?

Here is the response:

Hi David,

I shared your questions with Mickey Carroll, the Director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute and the spokesperson for our New York City polls. Mickey has responded to your questions. Here is Mickey’s response below.

Thanks for including us in your list. It’s always flattering to be mentioned. In answer to your three questions: (1) we didn’t ask an “are you aware” question because it would be superfluous about something that had been all over the New York news; (2) the question summed up the pro-and-con arguments; we could have asked a bare up-or-down question but we decided not to; (3) we always accept “don’t know” responses which in this case totaled a mere 6%, supporting point 1 above. Nice to hear from you. Cheers — Mickey

So, no “awareness” question because it had been all over the New York news! Very funny. People are notoriously uninformed about public issues, regardless of news coverage. A recent Newsweek poll, for example, found that 29% of Americans were unable to name even the current vice president of the United States. Right after the United States and other countries began attacking Libyan forces, a CBS poll found that 38% of Americans hadn’t been following the news about Libya (13% not at all, and 25% not closely). Yet, Quinnipiac wants us to believe that 94% of New Yorkers pay attention to the expansion of bike lanes? Sorry, I don’t believe it. And a good poll could provide the evidence, one way or the other. Why assume people are informed, instead of asking them?

Onto my second question – why not ask a straightforward unbiased question about bike lanes? The answer: “We could have asked a bare up-or-down question, but we decided not to.” Hmm. They didn’t, because…they didn’t. Quite an explanation.

What about my follow-up question: “By giving people reasons for and against the issue, reasons that they may not have thought about, aren’t you biasing the question?” No response from Quinnipiac.

Why the “forced choice” format (providing no explicit option for a respondent to say “unsure”)? The answer: “We always accept ‘don’t know’ responses, which in this case totaled 6%, supporting point 1 above.” Yes, but why not give the respondent an option to say “don’t know,” rather than subtly pressure the respondent to come up with one of the two offered options? No answer to that question.

The fundamental question I asked is this: “When you ask everyone the question, regardless of whether they even knew about it before the poll began, and then use a forced-choice format that pressures respondents to come up with an immediate answer, aren’t you artificially inflating the percentage of people who appear to have an opinion about the issue?”

No response from Quinnipiac on that issue.

SAYS “HATES” BIKE LANES: Within the 10 minutes on Grand Street, Joe, a driver for shipping company Gander & White, was almost hit by a bike rider going the wrong-way on the one-way street. When asked what he thought of the new bike lanes, Joe said, “I hate ’em. They’ve ruined the city.” Joe gave permission to be photographed, but declined to give his last name. (Credit: Rhonda Roland Shearer) |

The reason the poll sounds as though it is a PR release of the city administration is that, in my view, Quinnipiac simply didn’t take the time to design a good set of questions to measure public opinion on the matter. There was only one question – and a badly designed one at that – when almost any complex issue requires at least several questions to probe public opinion.

We need to know how many people had even heard of the issue, what experience they personally have had, if any, with the new bike lanes, and how intensely they feel about the issue, if at all. It would also be useful to know if they like the expansion in principle, but have some reservations about some of the specific bike lanes, or whether they support or oppose the plan completely.

There are many nuances in public opinion on most issues. Simplifying complex opinion into one biased, forced-choice question hardly serves the public – though unfortunately, the resulting numbers are often treated as though they represent the public will.

The issue was a hot one, and the single question generated a great deal of positive publicity for Quinnipiac University. For the University, the poll was successful. For the rest of us, it is unbelievable.

David W. Moore is a Senior Fellow with the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire. He is a former Vice President of the Gallup Organization and was a senior editor with the Gallup Poll for thirteen years. He is author of The Opinion Makers: An Insider Exposes the Truth Behind the Polls (Beacon, 2008; trade paperback edition, 2009). Publishers’ Weekly refers to it as a “succinct and damning critique…Keen and witty throughout.”