Handa Moses Akol (white beard & shirt with necktie in the middle) marching a "holy march" in 2003 with Ps. Henep Soap Lungil (in white shirt, on right) - two former enemies walking together united in the "holy march" leading their Christian flock at Punim near Nipa. As far as the eye could see, Christians are marching behind the banner. (Photo: MJ Kuwimb)

How do tribal communities in developing countries without functioning police, judges, law courts and prisons ensure social stability? This question is of perennial interest to anyone familiar with tribal societies. It is difficult for those of us familiar with such state institutions of law enforcement to imagine how people in tribal environments create order, particularly in dense populations like that of the New Guinea Highlands which also prizes individual political autonomy.

The popular image – traceable to Renaissance times, when Europeans first encountered tribal peoples – is of savages condemned to disorderly, even anarchic lives of constant violence and frequent bloodletting. A recent example of this image is portrayed and promulgated by Jared Diamond in “Vengeance Is Ours: What can tribal societies tell us about our need to get even?” published in the The New Yorker, April 21, 2008.

We seek to refute this portrayal in general and Diamond’s article in particular, which we believe amounts to nothing less than a betrayal. We were prompted to do this by the defamation of friends and relatives in the Was Valley of the Southern Highlands Province (SHP) of Papua New Guinea (PNG) who have, in Diamond’s article, been cast in such a caricature of tribal life as inveterate murderers, plunderers and rapists living in virtual chaos.

The Pig in a Garden: Jared Diamond and The New Yorker Series

Art Science Research Laboratory’s iMediaEthics is publishing a series of essays on the controversy surrounding Jared Diamond’s New Yorker article, “Annals of Anthropology: Vengeance is Ours.” The essay series titled, The Pig in a Garden: Jared Diamond and The New Yorker, is written by ethics scholars in the fields of anthropology and communications, as well as journalists, environmental scientists, archaeologists, anthropologists and linguists, et al. Paul Sillitoe & Mako John Kuwimb’s essay is tenth in the series.

Introduction to the revenge ethic

* * * * * * * * *

It is astonishing that media outlets still grant space to such a view of tribal life after a century of anthropological research has debunked it. Stateless or acephalous (headless – i.e. without authoritative officeholders) polities have long attracted attention and we have accounts of fascinating arrangements that substitute for central government. The Highlands of New Guinea have featured prominently in furthering our understanding of such tribal constitutions. So here we go, yet again, to rebut the savage misrepresentation.

We are not contending that disputes, aggression and killing are unknown – tribal people do not, any more than Westerners, live in a utopia. But an informed understanding of what happens in such conflicts challenges any sense of state smugness. After all, when it comes to the mayhem of their violent disputes, “civilized” states outdo all comers, as the current sorry Iraq and Afghanistan tragedies show. And if you value liberty, tribal constitutions maximize individual freedom beyond anything imaginable under democracy’s elected governments.

While all of us can probably relate to the motives that drive revenge,(1) we do not regularly act upon them because the nation-state has assumed the right to administer punishment on our behalf. However, before the emergence of nation-states in the West, and certainly before their imposition in Western colonial territories, there was no such social contract between citizens, and tribal communities regulated conduct in other ways, which sometimes included the right of revenge. In former colonial territories such as PNG, where the nation-state remains weak and fails effectively to honour its part of such a social contract, people understandably turn to their customary ways and principles to resolve conflicts.(2) These remain attractive because they are informal, inexpensive and effective, being sensitive to specific social circumstances and seeking to repair social rifts caused by all manner of wrongs, not needing resort to aloof judicial systems with their legal versus moral and civil versus criminal discriminations. The PNG government recognizes these attributes and the important role customary law plays in conflict resolution; the Constitution has adopted it as one of the sources of the nation’s laws(3). Accordingly, the PNG Parliament has enacted legislation to recognize customary practices(4) through the establishment of Village Courts to enforce them.(5) These Courts seek to uphold traditional ethic of payback.

The casual observer errs in thinking that revenge is an expression of uncontrolled emotions and savagery, whereas ironically it is an effective safeguard against such chaos and lawlessness. This erroneous conclusion often stems from seeking to understand revenge through inappropriate personal experiences and values, as Jared Diamond does. New Guinea people, such as the Wola(6) speaking Southern Highlanders, do not seek to justify vengeance by saying that they wish to secure justice and punish wrongdoers, such as for example the Simon Wiesenthal Center that seeks “to bring remaining Nazi war criminals to justice by offering financial rewards for information leading to their arrest and conviction.”(7) They subscribe to an altogether different logic. Revenge is a collective duty, integral to their stateless order. To understand why and the implications, it is necessary to know something about their tribal polity.The “2 Kina” Fight

We seek to further understanding of such political arrangements in the context of what has become known in the Wola area as the “K2 fight”, which is the conflict that Jared Diamond purports to use in his New Yorker article. In correcting the facts about this fight between Handa and Solpaem-Ombal of Margarima district in the SHP, we aim not only to put the record straight about what happened but also to show how Diamond’s account of never-ending war fuelled by hatred is wrong – a classic example of Western prejudice paraded before readers predisposed to think of tribal people as savages at the bottom of the social evolutionary ladder. [We have checked with those involved in the incident and they consent to us using their names,(8) albeit they had little choice, as Diamond’s piece already thrust them into the public domain.]

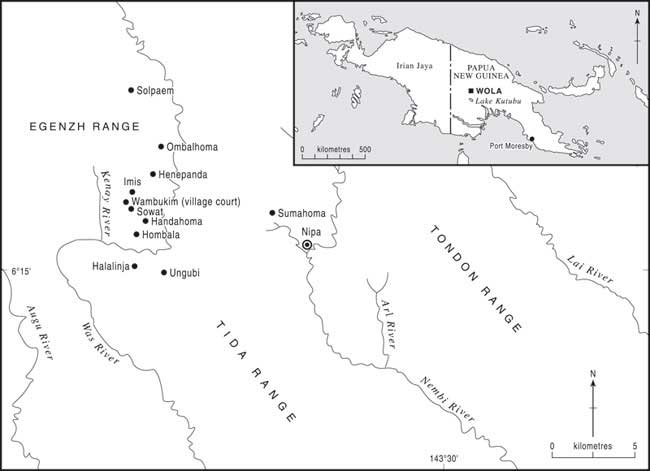

Map of the Wola region. Note that traditional names for villages are used. For example, a Google map would name Ombalhoma village, “Ombal”; Henepanda village, “Henep”; and Sumahoma, “Suma.” CLICK ON MAP TO ENLARGE.

Sometime in early 1993, two young Wola speakers from Margarima district, Kor Ungirip and Song Sowal, were playing a card game called “queen” with some others in the township of Mount Hagen where they had gone to find paid manual work, on either a coffee or tea plantation. During the card game, tempers flared as commonly happens when men gamble and some lose money. Song Sowal mislaid a two-kina (K2.00) note. He accused his friend Kor Ungurip of stealing it. A heated argument ensued. Kor punched Song on the jaw, injuring him badly. Failing to settle the conflict with prompt and appropriate compensation led to the “K2 fight”.

Similar fisticuffs happen in the United States, Europe and other parts of the world, where people turn to police officers and the state legal system to restore order. But in the New Guinea highlands, kin look first for support from one another in addressing a wrongdoing, often reaching a settlement through peaceful negotiations, but failing this they may go to the Village Courts situated in their regions. While these are part of the imposed state system, they have evolved to fit local ways. The PNG government instituted the system through the Village Court Act 1989 under which elected Village Court officials, called in Pidgin lus kiap (“magistrates”) and polis (“peace officers”), mediate in conflicts and help to determine compensation payments.(9) The system functions quite well, albeit insufficiently funded, officials receiving no pay for years.(10) Village Court officials are often well-respected members of the local community, such as Henep Isum Noah Mandingo, mentioned in Jared Diamond’s article, who served as a Village Court Peace Officer.

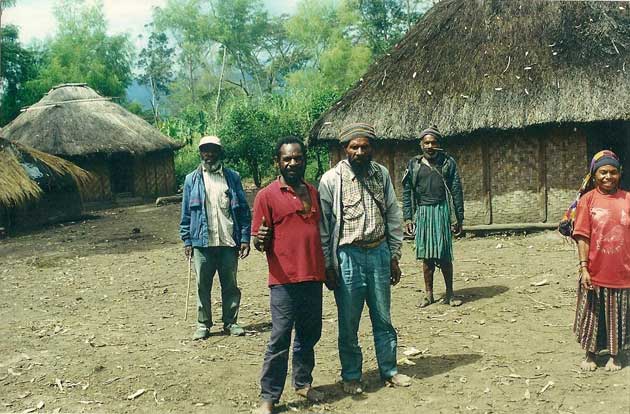

Left to Right: Henep Noah Isum Mandingo (2nd) Hulal Poraolli Nolle (3rd), Mongan Paonao (4th) Sanal Sar Wila (5th) & Hulal Ungur Nolle. Sanal Kaollu’s wife is in the far back. It’s 2001 at Aviamb Tea Plantation, Mt. Hagen. (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

|

|

Unlike modern prosecutors, judges and lawyers, the Village Court officials not only share the same cultural background and language as disputants, they are also aware of spoken and unspoken customary practices, innuendos, histories and personal backgrounds. Many are devout Christians whom litigants believe will be fair in their deliberations. The Village Court system is informal with no expensive legal representation, judges etc. It is locally accessible, unlike the Local, District or National Court system that follows British common law that demands strict procedures and specialized formalities.In the K2 altercation, Song returned to his village at Ombalhoma in the Margarima district, and from there he went to Mendi town where he spent some time in convalescence at the small hospital. When his relatives saw him hospitalized, they rallied to support him and demanded compensation – called ol komb – from Kor’s relatives through the Village Court situated at Wambukim – located between Hombala (Kor’s settlement) and Ombal (Song’s settlement). Kor and his friends had, in fact, paid Song and his relatives some money as a belkol (cool off) payment at Mount Hagen where the altercation took place. The matter might have ended there had Song not returned home and required hospital treatment, which convinced his relatives that the money received was inadequate given the seriousness of the injury.

The above political map, along with others–is readily available online. It shows that Nipa is far away from Margarima and is a separate political district. Margarima district is the location where Ombals and Handa live and the place where the “2 Kina” fight actually took place in 1993. Credit: Allen, B. 2007. “The setting: land, economics and development in the Southern Highlands,” in Conflict and Resource Development in the Southern Highlands of Papua New Guinea, State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Studies in State and Society in the Pacific. Edited by N. Haley and R. J. May, pp. 35-46. Canberra: Australian National University E-Press. Also see, L.W Hanson, B.J. Allen, R.M Bourke and T. J. McCarthy (2001) Papua New Guinea Rural Development Handbook, The Australian National University, Canberra, pages 89-97. |

Compensation demands are routine when someone physically injures another, even accidentally, and Village Courts have jurisdiction over such matters. When people are together, perhaps as travelers, they are expected to look out for one another’s welfare; if one suffers a serious injury or is killed, the others are held responsible and are expected to compensate the unfortunate’s kin. Relatives not only recognize an obligation to support kin in such situations, knowing they can rely on such support in turn if they ever need it, but they also have a vested interest in demanding compensation because they will share it among themselves, along with the injured party.

Conversely, if they face compensation demands, they will all be held liable and be expected to contribute. This complies with the ethic of reciprocity that characterizes social life in the Highlands, where the formal exchange of wealth marks all important occasions. Compensation goes beyond mere indemnification of a wrong; as an act of exchange, it marks the continuance of cordial relations jeopardized by a dispute. Compensation is also an effective deterrent to keep peace in such communities. The amount of compensation varies and depends on a number of factors such as the cause, nature and scope of the injury, and the status and relationship of the parties in the conflict.

In modern state societies, insurance serves some of the functions of compensation. But it somewhat dilutes the deterrent aspect of personal liability evident in Highland’s arrangements. Also, when an insurance company compensates an injured party, the social aspect of Highland compensation is absent. Moreover, the commercial aspect obscures the sense of a social duty of care towards other individuals. The injured party faces an insurance company staffed by persons interested not in their personal and emotional loss and welfare but in denying liability, or if liability is admitted, then in minimizing the amount payable. It is understandable that tribal communities in PNG prefer their customary system of compensation, albeit people may also resort to damages available through compulsory state insurance policies such as the Third Party Motor Vehicle Insurance Policy.(11)

In the Highlands, when injury or death occurs during a dispute, it is no longer a matter between two individuals but one that concerns the kin of both parties. In tribal logic, an injury or wrong to a person is an injury or wrong to their kin too. Any compensation paid is also shared by the victim’s relatives (sem). Likewise, when a person is responsible for an injury or wrong, their kinsmen are seen as wrongdoers too. In some senses this is not so different from the modern nation-state regarding criminal wrongs committed against a person as wrongs against the state. The unquestioning support of kin is a key feature of the social and legal order: it ensures that anyone who commits a wrong immediately faces a group defending the interests of the injured party. The same pertains with the revenge ethic. Without this response, the tribal egalitarian order would be compromised because the physically stronger would find themselves facing no opposition and could take advantage of the weak. In the absence of tribal protection, it would be a short step to the emergence of some sort of hierarchy, with certain persons taking power and dominating others, which is presumably what occurred with the emergence of states some six millennia or so ago.

A noteworthy feature of these arrangements is that collective responsibility results in kin striving to ensure that relatives behave in acceptable ways. The state takes this policing role away from communities, vesting it in state institutions mandated to administer justice, which may be seen to be protecting wrongdoers through such principles as presumption of innocence while victims of crimes go uncompensated. Another feature of the tribal legal order is that it compensates victims and punishes wrongdoers at the same time, with no demarcation between civil and criminal wrong. These features prompt communities to prefer to take disputes to the Village Courts rather than reporting them to the police, even if effective.

A Compensation Failure

In the K2 case, Song’s relatives demanded 20 pigs in compensation. The amount was based on a precedent set by the Village Court in a case between Pusi Wila of Henep and Hape La’a of Hombala in 1990.

Sanal Sar Wila in red shirt is brother to Pusi Wila – same father but different mother. Taken in 2001. Sar is from Henepanda. (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

In that case, Pusi Wila had broken Hape La’a’s jaw in a brawl while Hape was intervening to protect a female relative from Pusi’s unwanted flirting as she was walking home from a Goodnews Christian Church baptism ceremony at Samem Creek near Ombalhoma. Hape’s injury was more serious than Song’s. He required extensive surgery and his relatives flew him to Port Moresby for treatment. However, Song and his relatives thought that his injury was equally serious. Kor’s kin doubted it. In fact, some people with whom Song stayed during his medical treatment at Mendi confided to Kor’s relatives that they had seen him surreptitiously eating normally when he thought he was alone. That confirmed their doubts and led them to question the validity of the 20-pig compensation claim.A period of protracted and sometimes heated negotiations ensued between Song’s maternal relatives from Ombal sem (“family”) – with whom he resided – supported by his paternal relatives from the neighboring Solpaem sem and Kor’s paternal relatives from Handa sem, with whom he lived. The respective territories of these sem are on the opposite sides of a mountain ridge along the west bank of the Was River, some ten kilometers apart. The negotiations were conducted under the nominal auspices of the local Village Court at Wambukim, situated as described between the two territories, and which normally meets on Thursdays.

Not only do the lus kiap ‘court officials’ attend the Village Court, but so do the supporters of the disputants as well as some disinterested spectators. The hope is that this forum will lead to a resolution agreeable to both sides and an amicable settlement. Others present voice their opinions, like an informal jury. In some cases, kinsmen representatives of disputants engage in heated arguments, the disputants supplying information and challenging one another’s exaggerated accounts of actions that led to the dispute. If the Village Court gathering decides that one party is in the wrong, that party should concede and pay the amount of compensation determined as being appropriate or lose respect. The polis ‘Peace Officer’ and others may persuade compliance, but cannot use force. No one can compel acquiescence, which would detract from each individual’s political autonomy – albeit that freedom is inevitably socially circumscribed.(12)

It is understandable how kinsfolk might settle their differences in this way. They avoid openly violating fellow relatives’ expectations of self-regulation because to behave otherwise threatens not only reputations but also material interests. They observe shared conventions founded on an unspoken recognition that it is in the interests of all to control behaviour to facilitate the co-operation that benefits everyone. Sanctions that discourage antisocial behavior include withdrawal of support from wrongdoers, such that they forfeit the benefits of sociability that their actions threaten. When unrelated or distantly related persons come into dispute, as in the K2 conflict, such informal arrangements are less effective and settlement may prove more difficult.

During the negotiations-cum-dispute over compensation at Wambukim Village Court, prominent persons from Solpaem and Ombal, together with some sympathetic lus kiap, argued that the Hape-Pusi compensation had set a precedent. The hesitation of the Handa to acknowledge this, on the grounds that Song’s injury was less serious, infuriated his relatives. Nonetheless, Kor’s kinsmen acknowledged a certain culpability and were amassing pigs to offer in compensation. They had the “head pig” – that is, the largest beast tethered first in the display of animals traditionally staked in a line during a transaction – reckoned to be worth K1,000 and given by Jim Yalip, a Handa primary school teacher then stationed in Tari township. And they had the second pig, given by George Kuwimb, (elder brother of Mako John Kuwimb, co-author of this article), who was working as a motor mechanic in Tari. The Handa men agreed that following the collection of all the pigs contributed towards Kor Ungirip’s compensation, they would go the next Thursday to Wambukim Village Court and agree to the compensation.

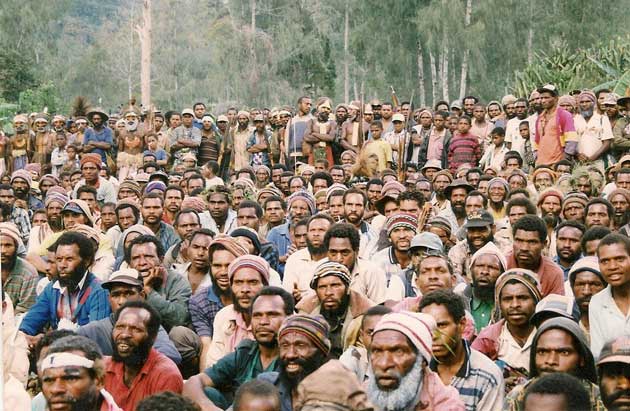

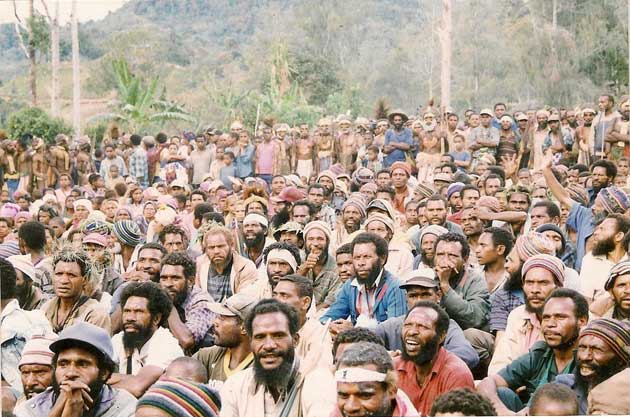

Part of the crowd at the Governor Dick Mune’s 1997 rally at Ombalhoma. Luim Lakis in white beard is an Ombal and the smiling man next to him in black beard is Mogan Pip from Ukaem who fought the Ombal as an ally of the Handa. Now they can sit together in peace as this photo shows. The man in traditional dress with a red pearl shell and white beard in the back next to a man in blue shirt and brim hat is George Kuwimb (my elder brother). (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

It was now May 1993, and the Handa prevarication was trying the patience of the Solpaem and Ombal. On the appointed Thursday, a number of Solpaem and Ombal men, armed with bows and arrows bypassed Wambukim and converged on Handa territory, probably with a view to intimidating Kor’s kin to pay by showing that they were ready to resort to arms. With tempers running high, it was a risky strategy. When Handa men saw the group approaching, they shouted at Song’s supporters to return to Wambukim, as the pigs and money were ready. But some of the Solpaem and Ombal men continued to advance. After shouting at them to turn back, Mawe Hond, the Handa lus kiap, grabbed his bow and fired some warning arrows, deliberately misfiring, to caution or frighten the men from advancing further in such a menacing way toward his homestead.Those arrows were the sparks that ignited the K2 conflict on Tuesday, May 11, 1993. Some of the Solpaem and Ombal men, now at a high pitch of excitement, returned the arrow fire. The confrontation escalated as several Handa men joined in. These were the first armed hostilities between these two tribes so far as anyone can recall, contradicting Jared Diamond’s claim of centuries of unending warfare. They were not ‘traditional enemies’, as the co-author of this report, Mako John Kuwimb, pointed out in a 26-page letter (April 21, 2009) to The New Yorker, “The Handa, Henep, Ombal and Solpaem clans never fought each other in all those years of my life, and never in the entire history of these clans other than the 1993 K2 war…the subject of Diamond’s distorted article.”

When such armed conflict erupts, serious injuries and fatalities are key issues. Either obliges revenge efforts, and fighting is likely to continue for some months as one side seeks to even the score. A state of san (pronounced sun) “hostilities” exists between the two communities. This brings us to lusimb (“revenge”), a principle central to armed conflicts.

The pursuit of Was hostilities: revenge ethic issues

The kin of anyone seriously injured (and likely to die) or killed violently recognize a moral duty to seek vengeance against those responsible and their relatives. To comprehend the logic of conflicts, and the K2 war specifically, it is necessary to understand why this injunction exists – not why individuals seek revenge, whether out of grief-fuelled emotion, fear of losing face, or sanctions against them. Some doubtless feel the desire for revenge as a burning personal emotion of the sort probably universal to humankind after the violent loss of a close relative; as Shakespeare put it in “The Merchant of Venice”: “If you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” But far more men rally to fight in a Wola conflict than ever experience this strong personal emotion.Tribesmen fight for other reasons, notably to prevent or deter others from subjugating them. An appreciation of the tribal revenge principle furthers understanding of how stateless orders contrive political equality, where none can gain power over others. These orders reverse the logic of states, in confirming Hobbes’ dictum that “freedom is power divided between many.” One of the outcomes of such revenge fuelled fighting is that it prevents any party gaining power; whereas in states, wars occur as one nation seeks to exert power over another, to force it into compliance, or to plunder its resources often in support of political-cum-corporate interests.

Ideally, persons should settle their differences without infringing one another’s equal rights. However, it is possible that if they cannot reach agreement, they may in anger and frustration resort to violence, as happened in the K2 case. The eruption of armed hostilities is instructive about the nature of the stateless polity. Generally, it occurs in the New Guinea highlands when one or several persons try to force their views on others, or when those who resist try in turn to compel the opposition to accept their standpoint. In short, when people seek to exert power over one another, violence can erupt. Each party predictably resists the other, as it is unacceptable in a tribal context for one party to exercise power over another – that is, to force others to comply with its wishes, depriving the other side of their freedom of action. In the K2 case, it was the Solpaem-Ombal men trying to force their views about the seriousness of Song’s injury, Kor’s culpability, and appropriate level of compensation on the Handa side, which resisted sparking the armed hostilities.

The revenge obligation kicks in if someone is killed in an armed confrontation or dies subsequently from injuries. After all, taking a life is the supreme expression of power and repudiation of freedom. While vengeance has a certain inevitability for those involved, all parties nonetheless regret its wretched and expensive outcomes: the violent loss of relatives as well as the heavy reparation burden that follows. No Wola person revels in savagery; as no sane person revels in war. All regret the violent death of relatives and allies.

The relatively infrequent occurrence of armed hostilities in the Was Valley is noteworthy. Far from the constant bloodshed Jared Diamond depicts, the conflicts that we have documented in the Wola Region of the Was Valley occurred 10 to 15 years apart (and none occurred between Handa and Ombal before the K2 conflict). The K2 fight was the fifth in living memory (one in 1930, two in the 1950s and one in 1960, with an approximate total of 33 fatalities over four generations).

Just as we should not exoticize tribal life, after Jared Diamond, so we should neither romanticise it. Putting a high premium on personal liberty potentially means aggressive behaviour to defend this political value. A readiness to resort to violence is necessary to defend yourself from others dictating to you against your will when you have a difference of opinion and cannot reach a mutually agreed compromise, and the other party tries to force its views on you. There are intriguing parallels with the U.S. gun lobby that advocates citizens’ right to bear arms in self-defence and the anti-federal government sovereign citizen/ militia movement, both of which purport to protect individual liberty. The threat of aggression is, after all, an aspect of political relations both in state and stateless societies. But individuals do not resort to violence lightly in the PNG Highlands given the personal costs in potential loss of life and resources, and usually only when amicable settlement through the Village Court system fails.

We can interpret the revenge principle as an institutionalised way of preventing any party seizing power and dispossessing others of their freedom of political action because as soon as someone kills another in trying to force him/her to comply with his views, he finds the deceased’s kin ranged against him. If there was no threat of revenge, the physically stronger would have access to power, being able routinely to coerce others. Such a situation would, as previously pointed out, spell the end of the free and egalitarian tribal order, which depends on no persons/groups having the opportunity to subjugate others to their will. The moral obligation to seek revenge checks this by rallying a group against any who attempt such force. While armed san begin with power struggles, once started they prevent any party from exercising power over another.

The organisation of fighting in the Was Valley

We see the absence of authority in the way men fight. While skirmishes involve some cooperation and coordination of actions, this is not in the Western military sense with a hierarchical chain of command. Predictably in a communal egalitarian context, each man fights as he thinks fit. Concerted group action results because individual acts have a common goal, not because anyone assumes a role of formal leadership. Some persons may post themselves on higher ground and try to shout warnings and guidance to kin about enemy movements; sometimes older experienced persons such as Mawe Hond on the Handa side, and Em Halip and Solpaem Tik Wandipe on the Solpaem-Ombal side. But this does not imply that someone who shouts directions is a commander. A few men may agree on the spur of the moment to coordinate their actions more closely, perhaps to outflank their enemies. The loosely coordinated actions of skirmishes also provide an element of unpredictability, even surprise. The group stays loosely together for protection and will rally to support any of its number injured.It is obviously necessary that individuals act in groups to pursue hostilities. But the constitution of these groups is less obvious. There are no conventions specifying that persons must support or protect certain groups (constituted by descent, residence, etc.). But neither are the groups that act together random alliances; kin interaction informs their composition. Action-groups may correspond closely with neighbourhoods but this does not imply that these are political units; it is just that people are more likely to join together with kin they live with than those living elsewhere.

Any collective act in the Was Valley similarly emerges from the interaction of participants, individuals acting voluntarily to give a group response, without anyone forcing his will upon others. (This is not to say that some persons do not enjoy more influence than others, but that is another story).

Those responsible for an argument that spawns armed conflict are the san te (“fight origin,” te meaning the base of a tree trunk) and it is around them that the sides come together. The san te in the K2 conflict were Song Sowal, on the Solpaem-Ombal side, and Kor Ungurip, on the Handa side. They and their neighbourhood kin acted as nodes around which sides and allies coalesced. (According to Diamond’s erroneous version of the K2 fight the san te – which he calls “owners” of the fight [conveying a quite a different meaning from what is understood in the Wola region] – were Daniel Wemp and Isum Mandingo, who came into dispute when a Handa pig spoilt an Ombal garden.)

The locales where people live comprise close-knit networks, extending beyond any one person’s social interaction into overlapping series of networks of relations. The words “tribe” or “clan” are often used for such a close-knit network of related families who live on a territory and share an ancestral history. Sometimes they are named after the original ancestor or a landmark such as a waterfall, mountain or river. Individual identity is associated with the name. If we take, Henep Isum Mandingo, Hup Daniel Wemp and Mako John Kuwimb: Henep is the name of Isum’s ‘tribe’, Hup is the name of a mountain from which Daniel’s ancestor migrated to settle with the Handa, and Mako is the name of a body of water formed by the Was River on Handa land. It is from this tradition that one can appreciate why Paul Sillitoe (co-author of this article) and his wife, who settled at Haralinja to undertake their anthropological research, were given the names Anda Pol and Hulal Saki by the Anda and Hulal ‘clans’ who live there. While they were foreigners, they were adopted into Anda and Hulal and accorded tribal support and protection.

The san te can rely on the support of their ‘tribal’ and neighbourhood relatives, with whom they interact daily, and some far-off relatives too, who may even enlist further persons via their networks. During the K2 conflict, for example, men from several locales came occasionally to support relatives. They came from Poiya, Ungubi, Komeya, Haralinja, Ingin, Endai, Obal, Hopang, Ya, Sumahoma, Pem, Kware, Sebiba, Somak and Pelhaori to support the Handa. And people came from Henep, Ukaem, Pol, Songura, Solpaem, Kambol, Kapendaga, and Aolamanda, among other places, to support Solpaem and Ombal.

This is part of the Dick Mune rally which my camera was not able to capture in the photograph immediately above. As you can see, my brother George is now on the right whereas in the above photo he is on the left. This shows the crowd was very large. The man in the cap on the front left is Johnson Iso Kuni, a Songura man (community school teacher) who supported the Solpaem-Ombal. (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

This is not to imply men from these places came en masse; many persons residing at these places have no direct relations with the Handa or Solpaem-Ombal, and some of them had a history of antagonistic interaction. Some split into two groups, for example, the Enja-Mongan of Ukaem and Aolmanda came to support both sides in the conflict. Indeed, not all residents on the same territory as the san te participate in the hostilities. Some get on with their own lives, cultivating gardens, building houses and so on while keeping a watchful eye on daily developments in the conflict. While kin recognize a mutual obligation to support each other in violent encounters and to seek revenge, it is up to individuals to decide when they will do so; no one can command them to fight. Some men only take up arms a few times during hostilities. Similarly, kin of the “fight origin” party who reside on territories elsewhere may lend support on some occasions and not others.Indeed it is usual today for some persons to refrain from fighting because of their Christian beliefs, (13) contrary to the image Jared Diamond gives in his New Yorker article. In the K2 fight, many men on both sides did not participate because of their Christian convictions. For example, on the Handa side, Michael Aolli Senge, Moses Akol Senge, and Panu Mom – all strong men in their 30s and 40s – did not participate at all, and on the Solpaem-Ombal side, men such as Hongol Palube, Wae Hapok, Ondowa Kapi and many others. Indeed, Christian influence contributed significantly to the short duration of the K2 conflict.

To appreciate the conduct of armed hostilities, it is necessary to remember that the number of fighters on both sides generally works out to be nearly equal in principle and practice. One cannot overwhelm the other by force of arms because when a fight starts, others rally in support on hearing the sounds of hostilities, so that more-or-less equally matched sides spontaneously emerge and engage one another. It is important to note that the tribal logic precludes any notion of defeat, unlike modern state warfare. There is only revenge, which is an expression of balance, measured in deaths. Here we see the ethic of reciprocity again. In the Was Valley, the aim is not to conquer the enemy but to achieve a balance of losses and damage, and to assert equality of relations by equaling the account. The “fair” outcome of the 2 Kina fight was two dead Handa men and two dead Solpaem-Ombal men, which allowed fighting to cease, neither side having a revenge debt, and the compensation phase to begin.

“2 KINA FIGHT” TIME LINE (*)

APRIL – MAY 1993

Between March and April 1993, the 2 Kina fight started.

• May 11, 1993

Fight started.

• May 13, 1993

Fukal Limbizu was shot in his sternum.

MAY – JUNE 1993

While waiting for Limbizu to recover, tension of the fight was still on and warriors from both sides were on guard day and night, but there wasn’t any actual combat (fight).

• June 23, 1993

Limbizu was discharged from hospital and sent home to Hurum Kiwa’s house. He collapsed and died. Limbizu’s time of death was 7:40 am. He was 57 years old.

JUNE – JULY 1993

After Limbizu’s death the fight erupted again and became worse. Allies of both sides (Handa and Solpaem-Ombal) arrived from neighboring villages.

• June 27, 1993

Sande was shot; he died quickly on this day.

• July 7, 1993

Soll was shot in chest on the left side and was taken to Mendi Hospital.

• July 21, 1993

Soll was discharged from Mendi Hospital and was taken back to his home. He was in the care of Apisi Kili who was teaching in Kundi Primary School. Soll was restricted from resuming his normal life in order for him to recover from his wound.

JULY – AUGUST 1993

Warriors from Handa, Solpaem-Ombal and their supporters from neighboring villages continue fighting. Many minor wounds were inflicted, but no major wounds were known to have occurred.

• August 8, 1993

Soll died on this day. Time of death was 4:45 pm. He was 47 years old.

AUGUST – SEPTEMBER

Fight continues and warriors planned to break through Henep’s territory because the Handas learned when the fight started, the arrow that shot Limbizu was shot from the taboo area which was Henep’s territory. Therefore they (Handas) broke through and started fighting on Isum’s land, despite his putting up warning signs to stay away and that no fighting was allowed. Isum only defended his land once they started burning his buildings and they shot and wounded him.

• September 3, 1993

Henep Isum, Kekel Ambiak, Walbo Wagilu and Wiyo Towap were injured. Mr. Let Hagop, the last brother of Soll, was wounded in the left eye. Mr. Kagep Nis was wounded.

• November 4, 1993

Kekel Ambiak died in Kainj Village, Lower Wagi, Margarima District. Upon his death the Ombal and Handas came to settle peace and stop the fight because all dead were equal on both sides (Two deaths on each side. On the Handa side were Soll and Limbizu . The Solpaem/ Ombal allies side were Sande and Kekel dead.

NOVEMER– DECEMBER 1993

Compensation started. Compensation was over and peace was in the area. There has not been any fighting in the area since this time.

The End of the 2 Kina fight

Fighting in the K2 conflict lasted about six months. By this time, many people were tired of the hostilities, which had seriously disrupted everyday activities. Armed men had to accompany women gardening. Relatives who found themselves on opposite sides could not interact freely. While it is typical in armed conflicts for men to side with those with whom they reside, they do not ignore relatives elsewhere. Costly in property and life, armed conflicts fray relations. The classificatory kin system, where people recognize a wide range of relatives, makes it inevitable that many related persons will find themselves on opposing sides.While distant classificatory kin may engage in combat, close relatives avoid fighting each other, and may even warn one another of peril. Consequently, the two sides do not comprise undifferentiated blocs or armies but fluid groupings of varyingly related persons with shared interests. Even the identification of two sides is difficult. Individuals come and go, and the sides may never be formed with the same membership from one encounter to another. It is possible that some persons may support both sides at different times, fighting one engagement with one and the next with the other. We can further see from this complex intermingling of relatives and loyalties across territories that the notion of one side “defeating the other” is inappropriate.

A decline in violent clashes gradually leads to recognition on both sides that armed hostilities are probably coming to an end, accompanied by increasing numbers of people agreeing with this view, losing their appetite for continuing the fight. Many individuals play an active part in ending armed hostilities where these interrupt social life for so many. In addition to those whose lives are particularly disrupted by the conflict, Christians are likely to play a leading part in ending hostilities. They are usually among the first to call for a halt of the fighting.

There is no formal declaration of peace enforced by one group over another as in state warfare where the victorious power enforces its will on the defeated foe. The notion of winner-loser is discouraged because this would lead to unending conflict, as the “loser” would insist on evening the score. Rather, an informal consensus emerges that further armed aggression is undesirable and unlikely. This phase is the san pol, the “fight sleeps.” Both sides know the opinion of the other communicated through persons related to both sides. For example, someone who has some of his mother’s father’s relatives supporting the other side may be in touch with them, and they convey views to and fro.

Councillor Aolnene Senge (my paternal first cousin) at Ombalhoma during Governor Dick Mune‘s rally in 1997. The K2 fight went to “sleep” so all the people in the Was Valley, including Handa, Ombal, Solpaem, Henep and others, gathered and mingled together freely as the photo shows. (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

There was an added incentive to cease the K2 hostilities that illustrates how state politics may intriguingly fuse with tribal practices, in ways unimagined by political theorists. There was an up-coming national government election to the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea in 1997. A Handa man called Paul La’a (brother of Hape La’a, whose jaw was fractured by Pusi Wila, mentioned above) was running for the Komo-Margarima Open Electorate, and to bolster his local support against other candidates it became widespread opinion that the K2 hostilities should end so everyone could rally behind him. Those not persuaded by Christian teaching to end the conflict were swayed by this political imperative.

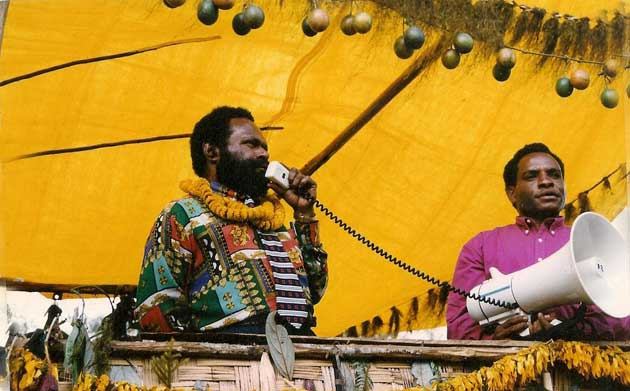

Governor Dick Mune speaking at the 1997 rally. The man holding the speaker is Sar Robert Penj, an Ombal ally who fought fearlessly in the K2 conflict. Robert is now a Christian. Governor Dick was killed in a nasty road accident, which sparked a conflict between the Nipas and Hulis. (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

While central government rule is generally not evident in rural SHP, the population engages in the election of National Parliamentary representatives every five years. It is an electrifying and often disorderly time across the PNG Highlands region. The parliamentary member is the only visible representative of central government in rural regions potentially capable of delivering basic social and economic benefits. Voters see supporting a candidate from their area or a neighbouring one as critical to securing any such services. The logic where no political ideology differentiates parties is to support the nearest candidate as most likely to ensure your community has better access to government funds. Candidates consequently win votes on the basis of their tribal and kin connections not their policies or ideological position. They work on strategies to build up their networks beyond their immediate areas, including even former enemies where possible. Although La’a lost to a Huli-speaking candidate from the north, his election strategy nonetheless contributed to the permanent cession of open hostilities.The chance of a fight “going to sleep” ultimately depends on the revenge tally. It is more likely to occur if the losses on either side are even, as in the K2 conflict. Also, immediate fatalities were few. Only one man, Sande Hameno, fighting on the Solpaem-Ombal side, died on the battlefield. Several sustained arrow wounds, some serious and ultimately fatal. It is usual for some unfortunates to die after receiving such wounds, perhaps from septicaemia. Among the wounded were Limbizu and Sol on the Handa side. Both suffered wounds that scarred over and appeared to be making recoveries – but it was thought that broken arrow tips remained in their bodies or, if not, their internal wounds were not fully healed. It was rumored their exertions during conjugal intercourse, in violation of a one-year taboo on sex after hostilities, led to their death weeks or months later. Similarly, Kekel Ambiak, fighting on the Solpaem-Ombal side, died from his wound several months later. Others survived severe injuries, such as Wiyo from Ya, whose mother is Handa, and who took an arrow in the eye. Settling the score is not winning or losing

The consensus was that four men died in the K2 hostilities: two from each side. There is no disputing this count. Sande died on the battlefield and the three others some months later from wounds. But counting the dead is not necessarily straightforward, for revenge accounting is a subjective business. An additional complexity, for instance, is where some people seek to include those who die from natural causes after the fight. For example, on the Handa side, Papua Mom, a young man of about 18 years of age, died with sudden stomach pains. His relatives alleged that the Solpaem-Ombal killed him through sorcery. On the Solpaem-Ombal side, Ombal Yaollip, a man in his 30s, died and his relatives claimed that Handa killed him in revenge for Papua through sorcery, although he showed all the signs of malaria.(14) Some other deaths on either side from natural causes were subject to such speculations. While some count these as K2 conflict deaths, not everyone accepts them nor agrees they call for compensation.This further contributes to the cessation of hostilities, allowing two sides to have different counts, one including some deaths, for instance from wounds, that the other does not. This is particularly so when people resort to sorcery to square accounts, which they do in absolute secrecy, subsequently attributing a death on the other side to such activity. Since there is no authority to declare which deaths should be attributed to a violent conflict, several versions may exist in different minds – each seeking to balance the account in their favor and feel that they have exacted vengeance. We can appreciate how this revenge score opacity helps hostilities to “go to sleep” because it is unlikely the casualties will, in fact, balance equally. This tradition helps avert otherwise interminable feuds.

If a conflict “goes to sleep” before some persons feel they have settled revenge scores, they may nurse enmity until further hostilities arise. When their former enemies become embroiled in a new conflict elsewhere, they may fight as allies on the other side just to have another chance to settle a score. If one of their old adversaries is killed, they may finally achieve revenge, although the death will ‘officially’ count towards the score of their allies’ new conflict.

For instance, during the K2 conflict, some Sumahoma men from the Nipa area came ostensibly to support Handa but took the opportunity to attack people at Henepanda (‘Henephouse’), who were previous adversaries who live between Handa and Ombal territories. Previously, Handa and Henep relatives had fought against Suma as allies. After the fight had ‘gone to sleep’ the Suma accused the Henep of using sorcery to kill one of their men but the arrival of the Australian colonial government and Christian mission had prevented them from avenging the death. The K2 fight presented such an opportunity. When the Handa side overran Henepanda during a large skirmish, the Sumahoma men razed some houses and damaged other property such as garden fences and crops, hacking down bananas, sugarcane, pandanus trees and coffee gardens. The Henep suffered ‘collateral damage’ and Henepanda became a san homa (“fight arena” – a razed area of trampled gardens, burnt houses and felled trees).

During the destruction, Noah Isum Mandingo from Henep, who was not initially involved in the conflict being a Village Court Peace Officer whose duty was to prevent tribal fighting, was drawn in when he sought to defend himself and his property at Imis (located on a hillock overlooking Wambukim). He received an arrow wound in the shoulder. (Isum recovered from his wound. He was never paralyzed by a spinal wound and never used a wheelchair, as Diamond alleges).

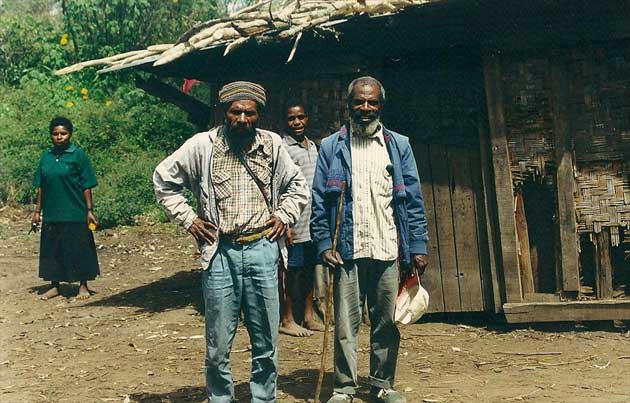

Isum with Hulal Ungur taken in 2001, at the same time as photo #2 above. “Isum was never in a wheelchair,” Mako John Kuwimb said. “I took these photos when I went there to take statements from witnesses on Pusi Wila’s death from electrocution while working on the Tea Plantation at Aviamp as a general labourer.” (Photo: MJ Kuwimb) |

This example of revenge delayed until new hostilities break out further illustrates the convoluted nature of conflicts because Handa men did not condone their erstwhile Suma ‘ally’s’ attack; indeed they had previously fought with Henep relatives as allies in hostilities against them.It is frowned upon, even dangerous, to talk about who kills or injures others during san. In the confusion of battle, often no one knows whose arrow was the fatal one, and other times several arrows hit the unfortunate slain. The code of not naming killers reflects the point that they are not individually responsible for fatalities. Rather, the san te (those responsible for the conflict) are held accountable (in the same way that the U.S. government is responsible when a soldier kills an Afghan or Iraqi civilian). It is critical that all deaths remain the responsibility of the “fight origin” party. It prevents each fatality leading to a new revenge obligation focused on the killer and protects the individual who fired the fatal arrow. The distorted article by Jared Diamond in The New Yorker, is not only in error referring to Daniel Wemp arranging to kill Isum and rejoicing when he was injured, but also contravenes this traditional convention of not identifying a killer.(15)

If kin knew who was responsible for killing one of their number, they may harbor feelings of revenge, potentially preventing a fight from “going to sleep”. The anonymity of killers helps in settling peace, as it reduces the chances of kin deciding to exact separate vengeance. It also reflects many men’s attitude to killing, which is not glorified but treated as a sad, if unavoidable, outcome of life in their stateless society (albeit some are said to enjoy the thrill of battle, just as western soldiers sometimes do). Those who have killed talk of having nightmares about it years afterwards, according to oral testimony.

When the K2 conflict went to sleep, potentially open hostile relations continued for some months. After that time, people started to speak of san ora sa – the “fight being over” – although it took years for some people to resume completely normal relations. History shows that the longer the san pol holds, the less likely open conflict is to occur again. There is a slow resumption of social interaction between enemies over a lengthy period of time, on a limited scale at first. Those related to both sides likely make the first, tentative open social contact. The risks they run resuming interaction depend on how closely they are related to the conflict’s san te parties. If they are only distantly related and meet somewhere else, they have little to fear; indeed, to attack someone in such circumstances is likely to spark a new san. Interaction between san te parties may remain tense for a long time and feature precautions (e.g., men only visiting the other’s territory in armed company), lest old enmities spark a fight. Armed conflict results in some long-term disrupted relations.

The practice of fighting as allies against old enemies perpetuates personal animosity, but the intertwining of kin networks prevents permanent enemy coalitions. Relations are dynamic; as new disputes occur and fights break out, old ones are forgotten. Unsettled revenge wishes are slowly disregarded, though possibly not in the lifetimes of those involved closely. The resumption of intermarriage between two previous enemy parties, after a period of curtailed interaction, marks the return to normalcy. In the Wola region, Christianity has had a considerable influence in prompting old enemies to forgive and forget old scores and live in peace. Furthermore, according to Wola wisdom, harboring revenge scores slowly eats away your heart and you should not keep hatred in your heart.

The Wola do not pass revenge scores down the generations, but they do pass down obligations to pay reparation to the relatives of those killed fighting up to four generations which, in itself, acts as a deterrent for fighting. They do not forget who supported them in time of need. Fighting not only costs lives and disrupts everyday life, but it obliges the san te and their relatives to pay out much wealth. Those responsible for san assume large liabilities, having to meet costly aol komb ‘reparation’ payments afterwards. They are held accountable for all those who die fighting or suffer serious injuries on their behalf, and they have to compensate their kin. This requires an extensive series of reparation exchange transactions, featuring large amounts of wealth: today, pigs and cash. These are usually so onerous that the descendants of a san te remains liable for many generations.

In modern nation-states, soldiers go to war in the name of the State, and the State pays the equivalent of aol komb to the injured or families of the deceased. Since the State collects money for the aol komb through taxation, citizens pay for the consequences of State violence. Those responsible, such as interest groups that manipulate the State to further their material or political objectives, do not bear personal liability, unlike individuals in this tribal order. From this standpoint, the tribal system ensures true justice and equity by requiring those responsible for armed conflict to pay a heavy penalty, which, if not fully satisfied, falls on their children, grandchildren or great grandchildren.(16)

These exchange obligations follow the same reciprocal logic as revenge – they seek to pay back relatives for their loss and support. They are a feature of social connectedness and kin relationships. Failure to meet these responsibilities can lead to further conflict, as it is tantamount to repudiating kin relations and associated obligations. A failure would also forfeit future support, a dangerous precedent in this tribal political environment where kin support is crucial to security. The threat of the exchange onus further encourages self-restraint, as noted, deterring costly violence in disputes with distant kin and strangers.

People in the Was Valley, as their history shows, do not enter into armed hostilities lightly. And they are not locked in continual conflict. Armed hostilities are the last resort when all other attempts at conflict resolution fail. The K2 fight took place because the Village Court failed to resolve the compensation issue. Although Handa men disputed the number of pigs claimed, they were prepared to pay some compensation. The Solpaem-Ombal men, frustrated at their slowness and thinking that they would outnumber the Handa men, resorted to a show of aggression that misfired. It is possible that if the case had come one more time to the Village Court, the fight would not have occurred.

The Wola tribal order dispenses justice fairly, untainted by some persons having more wealth or power than others. People seek to uphold these values of equality through the Village Court system. But if it shows signs of acting corruptly with respect to these, then tribal fights can result. The threat of armed conflict consequently acts further to encourage Village Court magistrates to promote and support even-handed decisions. These tribal communities treat all those involved in disputes equally and fairly, uncorrupted by some occupying positions of authority, based on social standing and superior wealth, and able to impose their views.

The revenge ethic that motivates fighting in the Was Valley guarantees individual freedom and equality. It has an entirely different logic to that behind the endless feuds previously fought in places such as Albania and adjacent parts of Europe and the Arab world. And when perforce people engage in armed conflict, it is not like all-out warfare or terrorism. As Mako J. Kuwimb noted in his detailed letter (dated April 21, 2009) to the The New Yorker, rebutting Diamond’s article: “We are not some unprincipled people without norms and morality attacking one another endlessly.” People in the Was Valley fight to defend their equal liberty. They are freedom-fighters with a difference: they fight not for freedom but with freedom. And they enjoy a liberty and equality unimaginable in nation-states.

References

* The Australian government clamped down on fighting in the Was Valley from the 1960s through 1975 independence, a fact which doubtless depressed the number of fights occurring in the region during that time. The tally of four wars with 33 dead that occurred in this part of the Was Valley from about 1930 until the early 1960s suggests that the number of conflicts that may otherwise have occurred would have been one or two, based on the pattern of one fight per 10 to 15 years. See Paul Sillitoe, “The Demography of a New Guinea Highlands Valley,” Asian Population Studies, Volume 2, Issue 3 November 2006, pages 271-294.See Paul & Jackie Sillitoe 2009 ‘Grass-Clearing Man’: A Factional Ethnography of Life in the New Guinea Highlands. Long Grove (Ill.): Waveland Press for further information on life in the Was Valley region.

PAUL SILLITOE is Professor of Anthropology at Durham University and Shell Professorial Chair of Sustainable Development at Qatar University. Sillitoe has long-standing interests in the Pacific, having conducted extensive fieldwork in PNG. In fact, Sillitoe was living in the Was Valley SHP, conducting fieldwork during the K2 hostilities and saw the fighting firsthand. He knows co-author Mako John Kuwimb from living in the region since the early 1970s. He knows Daniel Wemp and Noah Isum Mandingo. He first met Kuwimb and Daniel when they were young boys. Despite his world prominence as an anthropologist whose voluminous and meticulous research on the Was Valley is set to become an ethnographic classic, neither Diamond nor The New Yorker fact checkers ever contacted him.

Sillitoe’s background is in both socio-cultural anthropology and agricultural science. He specializes in economics, politics and social and environmental change, sustainable livelihoods and conservation, land issues and technology, human ecology and ethno-science. His current research interests focus on farming systems and natural resources management, appropriate technology, and development, both sustainability and relation to the natural environment, and cultural aspects and changing relation to the social order. Sillitoe is continuing his PNG research with a long-term program looking at human-environment relations, which comprises part of one of the most thorough investigations of such a subsistence farming regime ever undertaken. The next phase will incorporate a land-use database linked to satellite imagery.

MAKO JOHN KUWIMB is a Ph.D. candidate at the James Cook University School of Law, Australia, and a former adjunct lecturer for the University’s Native Title Studies Center. His doctoral research focuses on resource development, sustainable resource revenue management, and the contractual rights and obligations of parties involved in resource development projects. Prior to beginning his Ph.D. studies, Kuwimb was the First Secretary to the Minister for Lands & Physical Planning in the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea. He also worked as a litigation lawyer with Warner Shand Lawyers and later had a private legal practice. He earned a Master of Laws (Hons.) from the University of Wollongong, Australia, and a Bachelor of Laws (Hons.) from the University of Papua New Guinea. He is a member of the Handa tribe. He just moved back to PNG from Queensland, Australia, and lives in Port Moresby.

|

|

|

|

Notes |

|

| *. Rhonda Roland Shearer, with Jeffrey Elapa; Kritoe Keleba; Michael Kigl, “Real Tribes / Fake History: Errors, Failures of Method and the Consequences for Indigenous People in Papua New Guinea: Analysis and Report on “Annals of Anthropology: Vengeance Is Ours: What can tribal societies tell us about our need to get even?” by Jared Diamond, The New Yorker, April 21, 2008.” In preparation since 2008. Withheld due to litigation by request of informants. | Back |

| 1. We adopt the standard dictionary meaning of revenge to mean ‘the punishment of somebody in retaliation for harm done’, ‘something done to get even with somebody else who has caused harm’, and ‘the desire or urge to get even with somebody’: adopted from Encarta Dictionary online at http://uk.encarta.msn.com/dictionary_1861746345/revenge.html. | Back |

| 2. Unlike in the West where nation-states are autochthonous (“homegrown”), in developing countries they were imposed to pursue colonial objectives, so people generally do not see nation-states as entities serving their best interests, and this explains one reason why they prefer their traditional systems of social regulation over the imposed system. | Back |

| 3. Section 9 and Schedule 2.1 of the Constitution of PNG. | Back |

| 4. Customs Recognition Act 1963. | Back |

| 5. Village Courts Act 1989. | Back |

| 6. The Wola people of Nipa district and part of Margarima district speak the Angal Heneng Language sometimes referred to as Wola Angal (angal meaning language). | Back |

| 7. Quotation from Operation: Last Chance website (www.operationlastchance.org). | Back |

| 8. Naming in the Was valley region of the Southern Highlands is complex, as individuals can have several different names. The convention used in this paper is to give individual’s personal names, such as Song and Kor (equivalent to John and Peter), followed by their father’s names, such as Song Sowal and Kor Ungurip (equivalent to John Smith and Peter Brown), which is the system introduced by the Australian colonial authorities for census-taking purposes. The traditional system featured sem (“family”) names as prefixes to personal names. Christian names are adopted today after one becomes a Christian, such as Isum Mandingo named in Diamond’s article whose Christian name is “Noah”. | Back |

| 9. Sections 28, 29, and 30 of the Village Court Act 1989 define and set out the functions and roles of Village Court Peace Officers. | Back |

| 10. Mako John Kuwimb has acted for many of these Village Court officials to claim their outstanding entitlements from the PNG Government. He knows as a fact that many have not been paid for years. | Back |

| 11. Mako John Kuwimb has made successful third party insurance claims for persons injured in motor vehicle accidents from the PNG Motor Vehicle Insurance Corporation, but that has not stopped the kin of his clients from claiming customary compensation payments from the driver who was involved in the accident. Customary compensation systems exist side by side with the state-imposed or private profit insurance policy schemes. | Back |

| 12. If the losing party is dissatisfied, he or she is entitled to appeal to the Local or District Court in their area. Generally, appeal from a Village Court decision is very rare in the Wola region. | Back |

| 13. The Apostolic Christian Mission from the United States, which established a mission station on the bank of the Til Creek near Nipa, spread its influence between Nipa and Margarima districts after translating the New Testament Bible into the local language. | Back |

| 14. Yaollip died after he came back from Lake Kutubu, a malaria-infested area, and the symptoms of his ailment were that of one afflicted by malaria. It is generally known that men from the Was Valley died from malaria after they travelled to Lake Kutubu. The Was Valley is cool and malaria-carrying mosquitoes do not live there. Papua is suspected to have died from appendicitis. | Back |

| 15. Diamond’s article is capable of disturbing the peace and “waking up” the K2 fight that has gone to “sleep”, if not now, then in the future when an opportunity presents itself just as the Sumahoma men did at Henepanda. It is for this reason that we seek to present the facts so as to minimize the potential harm that it could cause if it goes unchecked. | Back |

| 16. In 2009, Mako John Kuwimb contributed one pig and US$1,000 towards the aol komb paid by his Handa clan to the members of Sanal clan for the death of one of their young men killed while fighting as an ally of the Handa in a fight between the Handa and Suma many years before Mako was born. | |