(Credit: Cleveland.com)

How iMediaEthics Got Interested

iMediaEthics’s publisher and founder, Rhonda Roland Shearer, met with the University of Iowa’s student newspaper this past spring when she was visiting as an adjunct lecturer. When meeting with the newspaper, Shearer learned of the Daily Iowan’s undisclosed policy to unpublish police blotter reports upon request.

As a result, iMediaEthics decided to examine similar policies for unpublishing and police blotters at a number of other college newspapers. While college students are still making decisions about future careers, they are particularly vulnerable to the possibility that a youthful indiscretion may turn up in a background check and prevent future employment opportunities.

And where might these mistakes be documented for future employers checking out applicants’ background? The college newspaper’s police blotter.

The alleged crimes in these police blotters are often nonviolent, such as use of a fake ID or underage drinking. iMediaEthics asks: Should these crimes be online forever, preventing the possibility of rehabilitation of the individual involved?

iMediaEthics’ summer intern, Corinne Segal, talked to representatives from college newspapers at ten U.S. universities with the highest enrollment to see how these campus papers handle police reports and unpublishing requests.

Methods

The National Center for Educations Statistics used fall 2009 college enrollment numbers to create this list of the largest schools in the U.S. iMediaEthics interviewed representatives from ten out of the 20 biggest schools on that list, excluding community colleges and those that had a large online enrollment.

We chose to interview representatives from student newspapers of large schools with the reasoning that these papers’ journalistic practices affect the greatest number of students in the U.S., though the same issues are also important to smaller schools and their newspapers.

We interviewed student newspaper representatives by phone, with the exception of University of Washignton’s the Daily‘s representative, with whom we communicated by email. For most papers, we spoke with an editor-in-chief and/or a section editor such as a news editor. (A more complete list of whom we interviewed is below.)

Some of the questions we asked:

- Does your paper have a regularly published police blotter? If not, why?

- Does your paper publish the names of students who have been arrested or accused of crime?

- Do you follow up on crime reporting, i.e., report the outcome of an arrest?

- Do you unpublish names, and if so, under what circumstances?

- Is your unpublishing policy publicly posted to make students aware of it?

- How popular on campus is your police blotter and/or crime stories?

People we interviewed and their titles during the summer:

- MN Daily (University of Minnesota): Taryn Wobbema (editor-in-chief)

- The Daily Collegian (Pennsylvania State University): Erika Spicer (summer crime reporter) and Lexi Belculfine (editor-in-chief)

- The Lantern (Ohio State University): Zack Meisel (editor-in-chief)

- The State Press (Arizona State University): Nathan Meacham (editor-in-chief), Danielle Legler (crime reporter)

- The Oracle (University of South Florida): Anastasia Dawson (editor-in-chief)

- The Daily Texan (University of Texas at Austin): Audrey White (News editor)

- The Independent Florida Alligator (University of Florida): C.J. Pruner (editor-in-chief)

- The State News (Michigan State University): Summer Ballentine (court reporter) and Kate Jacobson (editor-in-chief)

- The Daily (University of Washington): Hayat Norimine (crime beat reporter)

- The Indiana Daily Student (Indiana University): Brooke Lillard (editor-in-chief)

Overview of the Ten Newspapers’ Practices

Six of the ten newspapers iMediaEthics surveyed publish a regular police blotter. All ten newspapers publish some form of crime stories.

Nine of the ten newspapers will name students if that information is available or if there are formal charges. The exception is The State Press’ police blotter, which doesn’t identify people involved in crimes by their name. They will identify by gender, age and city of residence, however.

None of the ten newspapers will unpublish unless there is a factual error or someone’s safety could be jeopardized. Unpublishing would be handled on a case-by-case scenario

One of the ten newspapers, the Indiana Daily Student is the only one to publish its unpublishing policy.

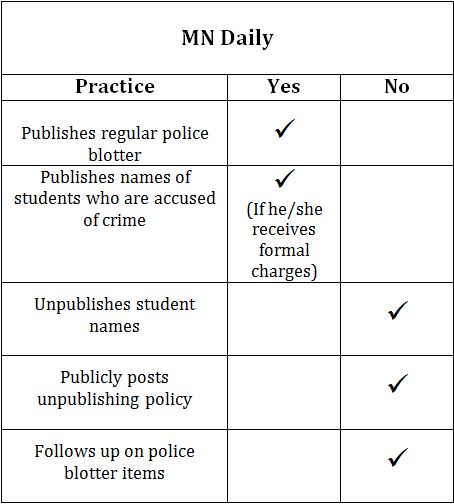

The University of Minnesota‘s MN Daily

The MN Daily, a student newspaper at the University of Minnesota, publishes a weekly crime blotter based on reports from the campus police.

The paper will publish names of students who are accused of crime in certain circumstances, according to editor-in-chief Taryn Wobbema. If the police formally charge a student, the newspaper will decide whether to name the student “based on the severity of the crime and the danger posed on people.” They will also publish names if the student in question agrees to talk on the record with the newspaper.

They do not unpublish names, but have “never had anyone ask” to do so, Wobbema stated.

The paper’s policy on unpublishing is not publicly posted or published. The MN Daily does not follow up on one-line police blotter items; however, they follow up on larger crime stories with extended articles.

Wobbema stated that she was unsure of how popular the crime blotter is with their readership.

See above The Minnesota Daily’s policies for reporting on crime. |

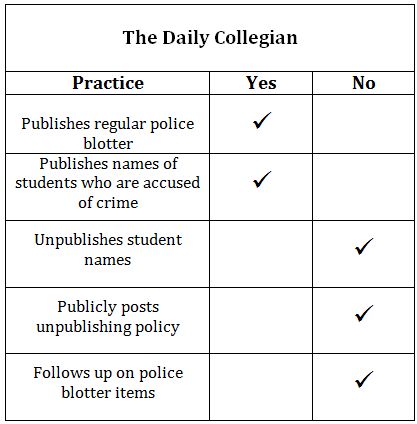

Pennsylvania State University’s Daily Collegian

The Daily Collegian is the student newspaper of Pennsylvania State University. The paper prints a daily police brief.

They publish the names of students who are accused of crime “as long as charges have been filed against the student and we have court documents to back this up,” editor-in-chief Lexi Belculfine stated.

Belculfine noted that the newspaper won’t “use the word ‘suspect.'” They do not unpublish names, unless the original report was incorrect. The paper’s policy on unpublishing is not publicly posted or published. The newspaper will publish follow-up stories on “some blotter reports, depending on their severity — for example, assault and other violent crimes, or crimes linked to a string of other incidents,” Belculfine stated.

Spicer noted that “certain cases” that the paper covers are “popular online.”

See above The Daily Collegian’s policies for reporting on crime. |

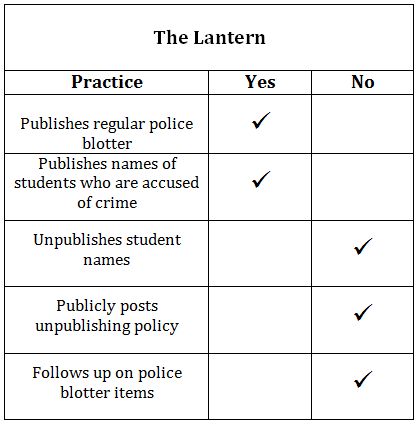

Ohio State University’s The Lantern

The Lantern, Ohio State University‘s student newspaper, publishes a police blotter once a week, according to The Lantern’s Thomas Bradley.

The paper does publish the names of students who are accused of crime, and does not unpublish names unless there is a “legal precedent,” (“if the inclusion of someone’s name puts anyone at risk or jeopardizes a case” but that is a “rare occasion,”) Miesel stated. Unpublishing is an exception to the rule.

The Lantern does not publish or publicly post their unpublishing policy and does not follow up on police blotter items. It does follow up on extended crime stories, according to Miesel. He cited the incident of Woodfest, a “block party” where three students were “charged with assault on a police officer,” as an example of their extended crime coverage.

Miesel stated that the police blotter and crime stories are “pretty popular” among the paper’s readership.

See above The Lantern’s policies for reporting on crime. |

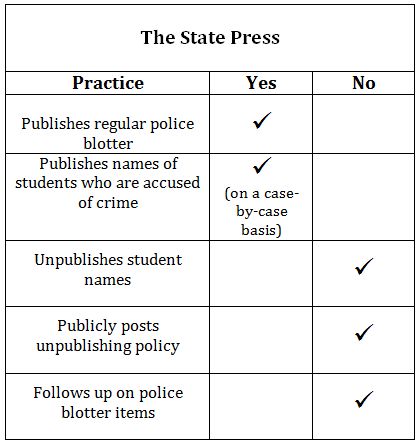

Arizona State University’s The State Press

The State Press is the student newspaper of Arizona State University. They publish a daily police blotter, Monday to Friday.

The paper does not publish the names of people involved in crimes for their police blotter – instead, they print the suspect’s “gender, age and the current city they live in,” editor-in-chief Nathan Meacham told iMediaEthics. If the newspaper wants to extend coverage of a particular crime, the newspaper will then report the name of the suspect, according to Meacham. “Our biggest reports for crime around campus do name suspects,” Meacham wrote. “Normally the crime suspects are city residents that commit crimes related to or on campus.”

The Stae Press does not unpublish names, and their unpublishing policy is not publicly posted. The State Press does not follow up on police blotter items, Meacham stated.

Meacham added that the paper’s police blotter is in the “top five” of the most popular items of the day.

See above The State Press’s policies for reporting on crime. |

University of South Florida’s The Oracle

The Oracle, University of South Florida‘s student newspaper, does not have a police blotter because it has an insufficient number of reporters to do so, editor-in-chief Anastasia Dawson said.

When they publish stories about campus and local crime, the newspaper publishes names on a case-by-case basis, according to Dawson. Dawson added that the newspaper “usually” won’t name sexual assault victims.

Dawson noted that the university does publish “an hourly activity log on its website” of campus police incidents. Dawson wrote:

“As journalists we have a duty to keep our public informed – and our public is comprised of juveniles and young adults. If someone is involved in a documented crime (i.e. theft, hazing, motor accident) we will publish names and clarify if they are suspects, convicted of the crime, etc. When covering crime, we verify and attribute all names and facts with police reports. We always try to consider who could be put at risk by what we publish, however our stronger loyalty is to our readers and victims of heinous crimes.”

She stated that she has never received a request to unpublish a student’s name from a crime story, but that the newspaper would not unpublish unless there is a factual error that would warrant unpublishing. If the newspaper reported on charges that a student was later cleared from, she explained the newspaper “would make an editor’s note on our already published online story. If we got something completely wrong, we would take it down or correct it with an editors’ note.” But, she notes these scenarios are “all circumstantial.”

This policy is not publicly posted. Dawson claimed that The Oracle follows up on the crime stories they report.

The paper’s crime stories are usually fairly popular among readers, Dawson stated.

See above the Oracle’s policies for reporting on crime. |

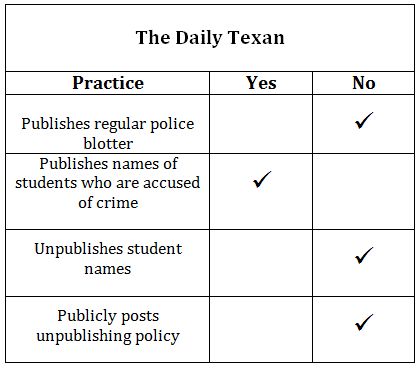

University of Texas-Austin’s The Daily Texan

The Daily Texan is the student newspaper of University of Texas at Austin.

The paper does not have a regular police blotter, but does publish crime stories, according to summer news editors Audrey White and Matt Stottlemyre.

They publish crime stories in which they do not usually name suspects, because the names are not available in the police record. If names are available, they will publish them, White said.

They do not unpublish students’ names from crime reports. White was unsure of The Daily Texan’s policy on following up, since, she said, most crime reports focus on a trend of crime on campus instead of individual crimes.

However, if a report did not receive proper follow-up, they would insert an editorial note online reporting the outcome of the case.This policy is not publicly posted.

The Daily Texan’s crime stories are usually “well-viewed” among readers, White said.

See above The Daily Texan’s policies for reporting on crime. |

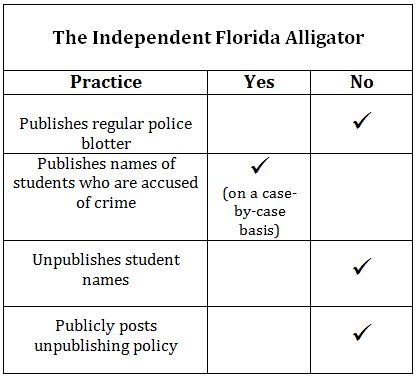

University of Florida’s Independent Florida Alligator

The Independent Florida Alligator, the student newspaper at the University of Florida, does not publish a police blotter. The paper publishes the names of people who are accused of crime in news stories, but may decide on a “case-by-case” basis to cut the name from the report for a minor crime, according to editor-in-chief C.J. Pruner. However, Pruner notes “we very rarely, if ever, decide to leave the name of the accused out of the paper.” According to Pruner, “the only ones who pretty much receive name protection are sexual assault victims, not those accused of the crime.”

They do not unpublish names unless the report was factually inaccurate. The Independent Florida Alligator does not publicly post their unpublishing policy.

The paper follows up on most crime stories but does not follow up for “smaller” crimes such as a DUI; however, most crimes that they publish are “serious” enough for follow-up, Pruner stated. He noted that “graphic” stories such as reports on a sexual assault tend to be fairly popular in the newspaper.

See above The Alligator’s policies for reporting on crime. |

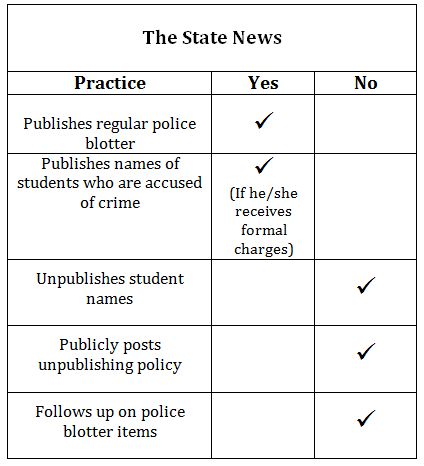

Michigan State University’s The State News

The State News, Michigan State University’s student newspaper, publishes a police brief Monday through Friday. The briefs include the date of a crime, the age and gender of a suspect, and notes whether they are a student, “university employee,” or unaffiliated with the school. The State News will only print the name of an arrested individual if the student is formally charged with a crime. At that point, their arrest becomes “public information” and the paper will not unpublish the name, according to court reporter Summer Ballentine. The paper does not post its unpublishing policy.

The State News will follow up on news stories but most police blotter items aren’t “interesting” enough for follow-up, Ballentine said.

The State News’ city editor, Emily Wilkins, added that the newspapers “sometimes” will run follow-up reports on certain police briefs “basedd upon the severity and charges of the reports.” Wilkins noted that “police briefs are relatively popular among commenters on our website.”

See above The State News’s policies for reporting on crime. |

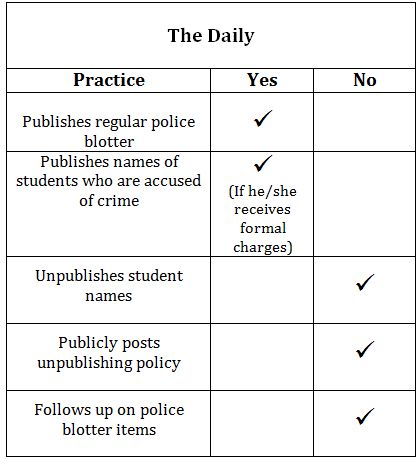

University of Washington’s The Daily

The Daily, a student newspaper at the University of Washington, publishes a weekly crime blotter. The blotter notes the date and in some places, the probable time of a crime. It also states the gender of a suspect and/or victim. The paper will only publish the name of an individual in connection with an a crime if they are formally charged, but will not unpublish the name unless keeping it in the archives will put the student in physical danger. The Daily does not post this unpublishing policy.

They follow up on “big incidents” but not for a crime that “people wouldn’t be interested in,” according to an email from crime beat reporter Hayat Norimine. As Norimine explained, “most of the crime we follow doesn’t need following up and they are one-time incidents.” The crime blotter is “probably not that popular” Norimine wrote.

See above The Daily’s policies for reporting on crime. |

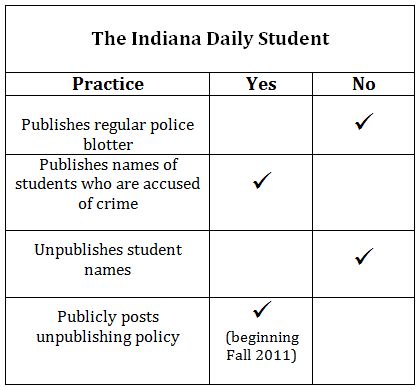

Indiana University’s Indiana Daily Student

The Indiana Daily Student, a student newspaper at Indiana University, does not have a regular police blotter but publishes crime reports based on information from the Bloomington Police Department and the IU police department.

The newspaper’s editor-in-chief, Brooke Lillard, told iMediaEthics that the police department provides the newspaper with a blotter and reporters will either go to a “daily press meeting” or call the police for more information about certain cases.

The paper will name students who are arrested or accused of crime and does not unpublish names. If a story contains factual errors or needs relevant information to be added, the newspaper will do so in an update, Lillard told iMediaEthics.

Lillard explained the newspaper currently will not unpublish under any circumstances.

Newsroom adviser Ruth Witmer clarified that the newspaper is student-run and an “independent auxiliary — editorially and financially independent.” Because of that relationship, Witmer notes students cannot appeal unpublishing requests to the university. Witmer explained that the newspaper simply won’t unpublish police blotter reports becasue the students or former students are “embarrassed” and don’t want to be “associated with their college behavior.” She wrote:

“The editors are human and they understand people’s concerns and regrets. But they’re trying to be responsible journalists and public servants. Once you start chipping away at your informational archive – because people disapprove of the content – what are you? How much will people trust you? What would be left the read?”

The newpsaper has, however, talked about “scenarios that haven’t but could happen” in terms of unpublishing. For example, Witmer noted the newspaper has considered whether it would unpublish if information published online could “put someone in danger somehow.”

In the fall of 2011, the school’s student media groups, including the Indiana Daily Student, will publish an updated version of its code of ethics, Lillard noted. In that up the newspaper will make its unpublishing policy more public, Lillard noted.

Crime stories tend to be “pretty popular,” Lillard said.

See above The Daily Student’s policies for reporting on crime. |

In Conclusion:

iMediaEthics recommends that campus newspapers establish a clear policy for naming people involved in crimes in their crime blotters. The State Press’ practice suggests a good model: In non-violent crimes reported in the police blotter, the newspaper doesn’t name those accused, but does provide age, gender and city of residence. This practice allows the newspaper to avoid unpublishing information and being burdened with following up on smaller police charges that may later be dropped. Is naming student offenders of non-violent crimes really newsworthy or in the public interest?